Hey Bulldog*

Some firearm designs are iconic, almost mythic. One of those was introduced in the early 1870s, and was widely carried both by military forces and civilians, and is credited by many firearms historians as being a critical factor in the ‘taming of the West’.

No, I’m not talking about the Colt SAA. I’m talking about the SA/DA Webley No. 2 in .450 Adams/CF (center fire), commonly referred to the Bulldog, designed as a self defense revolver small enough to carry in a pocket. Like this one:

That pic doesn’t give a good idea of the small size of this big-bore revolver. But overall it’s about the size of a modern J-frame. Here are a couple of images of me holding it:

The serial number of this particular gun (23905) indicates that it was made in the first batch of guns (serial numbers 20,000 – 25,000 were made 1872 – 1876). Made in Britain, these guns usually had the legend “BRITISH BULL DOG” on the top strap, except those sent for sale in the American market, which were marked with the importer/seller’s name. This is one such example, with the legend “LIDDLE & KAEDING, SAN FRANCISCO” on the top strap:

I assume that the decorative elements are stamped, but this is the only one of this era I’ve seen with it, so I may be mistaken.

While many of these guns were made, not many today are in sufficiently good condition to be shot safely. Partially this is due to the fact that the original black powder cartridge, containing a 255gr bullet traveling at about 650fps (for about 211ft/lbs of ME), was superseded by more powerful cartridges that fit the gun and would cause damage if not catastrophic failure. You can see how this could happen if you look at the thinness of the webbing between the chambers in the cylinder:

However, this example seemed solid and in good condition upon examination. There were no signs of damage or significant wear on the functional parts, and the lock-up of the cylinder was good, with only minimal play. We had .450 Adams/CF ammo loaded to original spec (made using .455 Webley brass cut down), and decided to give it a try:

A note about that ammo name: The cartridges were .450 Adams, designed by another company for their firearms. But evidently Webley didn’t want to have another gun manufacturer’s name on their guns, so decided to just call the round the .450 CF, and marked their guns such. That may have contributed to the use of more inappropriately powerful rounds later which damaged the guns.

The gun is very well designed. The ramrod swings over to eject spent cases, then the retaining clip through which it passes can be shifted to allow removal of the cylinder for cleaning. While the grip design is different from modern revolvers, it isn’t unpleasant in the hand. Felt recoil is substantial, but mild compared to lightweight modern small revolvers such as a J-frame in .38sp. In terms of power, 211 ft/lbs of Muzzle Energy is about half to two-thirds of what modern pocket guns typically generate — certainly effective, particularly given the state of medical knowledge at the time these guns were popular.

While the sights are simple, just a blade on the front and the typical trough along the top strap, they’re adequate for a self defense gun. All of us were able to keep rounds on the black of an 8″ target at about 10 yards without a problem.

Here’s shooting it:

The Webley No. 2 didn’t have the effective range or power of the Colt SAA, but it was well suited to its role as a reliable close-range self-defense firearm. While it was never widely issued as a military side-arm, British officers would frequently purchase it separately to carry, and many were sold in the civilian market. It was so popular that the design pattern was copied and produced in many countries, earning its iconic status. It was a real pleasure to have a chance to shoot an original.

Jim Downey

*With apologies to The Beatles.

That takes balls.

I recently picked up a little Pedersoli Liegi Derriger kit. One of the other BBTI guys has one of these things, and I’ve always considered it a cool little piece of firearms history. Cap & ball firearms technology came along in the early part of the 1800s, supplanting flintlocks and earlier ignition systems. The Liegi design was very popular as a basic pocket/boot/muff small handgun, because it was relatively easy to load and carry, and lethal at close range.

The interesting thing about the Liegi is the loading system: you unscrew the barrel, load the powder charge in the chamber, place a round bullet on top of the powder, then screw the barrel back into place. It’s simple and fairly foolproof, and doesn’t even require a powder measure — you just fill the chamber with black powder and it’s the correct amount. Once the gun is loaded and the barrel is in place, you draw the hammer to half-cock, place a cap on the nipple, and the gun is ready. Here’s a short video showing all the steps:

In addition to doing the minor prep work on the walnut stock of the gun, I wanted to add some laser engraving on the side panels. Because it amused me, I decided to use the same basic pattern as I had used for the grips of a very modern handgun, my Customized Timberwolf G21. Here’s a pic of the finished product, and on the next page are pics of the process and comparisons to other small handguns I have:

Review: S333 Thunderstruck.

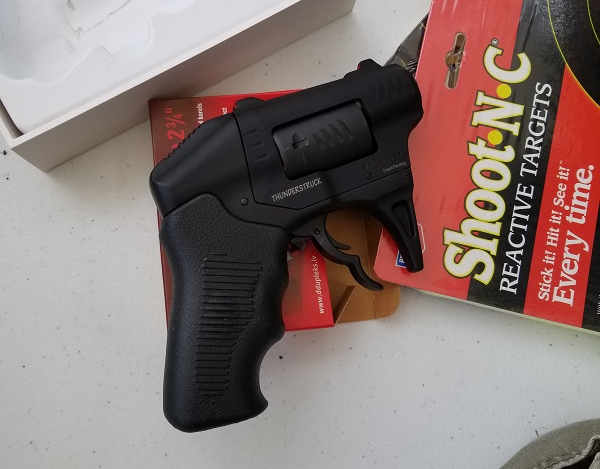

This is the Standard Manufacturing S333 Thunderstruck revolver:

It’s an innovative, 8-round revolver which fires two rounds of .22WMR (.22mag) with one pull of the trigger.

OK, if you like this not-so-little handgun, you might not want to read this review. Just move along and save yourself some time.

No, really.

If you have to think about it, here’s another pic to give you some time:

The actual S333

* * *

For those who’ve stuck around …

… good lord, don’t buy one of these things as a self/home defense gun. If you want it just because it’s kinda geeky and weird, then cool. If you want to actually use it, go spend your money on almost anything else. Seriously.

Why do I say this?

Because, for the ostensible use of the gun as a self/home defense tool, it is almost entirely unsuited. Yeah, that’s my biased opinion, on having shot the thing.

Oh, you want details? Reasons for this opinion? Fair enough.

When I first heard of it, I saw that it was .22WMR, out of a 1.25″ barrel. Now, since it is being shot out of a revolver, you can add in the length of the cylinder, and come up with an overall barrel length of about 3″.

.22WMR out of a 3″ barrel isn’t exactly useless. I mean, it beats harsh words. And, in fairness, it beats your typical .22lr. A little. You can expect about 100-110ft/lbs of energy from it. The best-performing .22lr from the same length barrel is about 90ft/lbs. Same for .25ACP.

And, if you think in terms of having two such bullets fired simultaneously, that gets you up to about 200-220ft/lbs of energy. Not impressive, but I wouldn’t want to be shot by it. I mean, it’s better than .32ACP.

Well, it would be if for one big problem: keyholing.

See, with such a very short barrel, the .22WMR bullets aren’t stabilized. They come out of the barrel, and tumble. If the bullet tumbles upon leaving the barrel, it will quickly lose energy to aerodynamic forces. And likewise, if it hits something more solid, it will also lose energy more quickly. Which will really mess up their effectiveness in penetrating deep enough into an attacker in order to be effective. Because, remember, this is supposed to be a self/home defense gun.

See for yourself:

keyholed!

Yeah, of the 8 bullets I fired (from about 5 yards, aiming at the center of the target), 7 have keyholed.

This is something that almost every review video I watched also noted. The S333 keyholes at least 50% of the time, and usually more.

So let’s go back to the comparison with .32ACP. Keyholing can happen with any caliber and almost any gun, but it tends to be rare in well-designed guns and properly matched ammunition. So, usually, you can rely on fairly consistent penetration out of .32ACP. Which, according to independent testing by Brass Fetcher, will give you 7-10″ of penetration in 20% ballistic gel. And .22WMR will do about as well.

But not if it keyholes. Which it does, out of the S333.

Now, Standard Manufacturing has said that this is something that they’re working to correct. So perhaps later versions of the gun will not have this problem.

I still wouldn’t want it. Why?

The S333 is as large and weighs (18oz) as much as many common compact 9mm semi-auto handguns. It’s larger and weighs more than most small .380 semi-auto handguns. It’s larger and weighs more than most small frame .38/.357 revolvers. Any of those alternatives offer much more potent cartridges, even in comparison to two simultaneous .22WMR rounds. And with the S333, you have four shots — your typical small revolver will be 5 or 6, and small semi-auto guns are typically 6 or more.

The S333 is also awkward and difficult to shoot. The unusual “two finger” trigger really changes how you can grip the revolver, changing how you aim and control it. It’s also a very long and very hard trigger pull — something in excess of 12 pounds, by most reports. If, like most people, you want to use a second hand to support your shooting hand (which is even more necessary when you only hold the gun with your thumb and two small fingers), about the best thing you can do is grip the wrist of the shooting hand in a modified “cup & saucer” style grip. Otherwise, the fingers of your supporting hand will be in the way of the trigger coming all the way back, which is necessary for it to fire.

Here, see what I mean with this short video of me shooting it:

I think the awkwardness of the grip and the two-finger trigger explains why most people tend to shoot the revolver high and to the right when they first encounter it. All three of us at BBTI did. Almost every review video I watched had the same thing.

I’m sure you could learn to adapt to this, and develop a secure and reliable method of shooting the gun with practice. But as a “grab it and use it” self-defense gun, it’s a problem.

One minor note while the video above is fresh in mind: did you notice the amount of flash in two of the shots? Yeah, that’s another factor of such short barrels with the .22WMR. That was while shooting it on a typical partly cloudy day in the middle of the morning. Not a major problem, but something to register.

One last thing: price. As you can see on the first pic, this particular S333 sold for $419.99, which is just under the MSRP. So while it isn’t really pricey, it isn’t cheap. In fact, it seems to be a very solid and well-made gun. The fit and finish were good. The minor problems we had with it were probably just because it was brand new (it hadn’t been fired previously). The trigger is, as noted, long and very heavy, but reasonably smooth if a little mushy. So, overall, if you wanted one of these just because it’s unique and quirky, then I think it’s a reasonably-priced gun.

But if you are looking at it as a self/home defense gun? Or even as a “back-up” for that use?

I think you have much better options.

Jim Downey

The Cunningham Speed Strip

Anyone who has considered a revolver as a self-defense option has confronted the question of whether, and how, to carry spare ammunition for it. Loose cartridges are just a pain to deal with, and take forever to reload. Speedloaders are great, but more than a little bulky. Commercial ‘speed strips’ are less bulky, are commonly available at a reasonable price, and are a big improvement over fumbling with loose rounds, but can still be awkward for reloading quickly. That’s because while they hold six cartridges, they’re difficult to position such that you can load an empty cylinder quickly — the close-packed cartridges actually get in the way. One common trick for using a speed strip is to only put two pairs of cartridges in it, with a gap between the two sets and the last position empty — that way, you can always quickly load two sets of two adjacent chambers in the cylinder of your revolver. This technique is perhaps best known due to defensive revolver guru Grant Cunningham.

Well, after recently taking a class with Grant, and learning this technique, I set out to make a more functional speed strip which would completely and quickly reload any revolver. One that almost anyone can make on their own, with minimal tools and expense, and customized to their revolver, whatever cartridge it shoots and whatever the capacity of the cylinder. I jokingly call it the Cunningham Perfect & Adaptable Speed Strip for Any Revolver regardless of Caliber or Capacity. More seriously, I’ll refer to it as the Cunningham Speed Strip, (CSS for short.)

Here some pics of what it can look like:

And this is how you make it.

YOU’LL NEED:

Tools

- A pair of common pliers

- A hammer of almost any type

- A pair of scissors or utility knife

You’ll also need

- A Heat Source (just about anything from a hair dryer to a blowtorch will do — you’ll see)

- An empty cartridge case for your revolver

- A pen or pencil

- A sheet of paper (really, just a scrap)

- A scrap piece of heavy cardboard or wood

- Suitable piece of inexpensive common vinyl (more on this to come)

PROCEDURE:

Select your vinyl. A wide variety of commonly available types of vinyl will work. If you look at the examples above you’ll see a piece from a 1/2″ ID vinyl tube, a piece of vinyl floor runner, and a piece of vinyl sheet used to cover food for microwaving. In other words, a wide variety of vinyl materials are likely to work.

So experiment a little. What you want is to find a vinyl which is flexible (not rigid/brittle) and sufficiently thick to hold cartridges in position, but will easily pull away when you have the cartridges in the chambers of the cylinder. The vinyl tubing is the one I like the most, and is 1/16″ thick. It has a slight tackiness to the surface I like because it makes it easier to use. The vinyl sheet is about one-third that thick, and the vinyl floor runner is somewhere between the two (though a little too flexible for my tastes).

Now, realize that it’s likely that any of these materials will tear after repeated use. These aren’t meant to last forever … but each of my prototypes have held up to at least a dozen uses so far. The idea is that they’re cheap and easy to make and replace.

Cut the vinyl to rough size. You want a working piece that you can trim later. Here’s what the tubing looks like when cutting:

Make a paper template. It’s difficult to mark most kinds of vinyl. So the easy thing to do is to make a paper template of what you want. For a J-frame, you want two sets of paired cartridges and one solo, with gaps in between the sets (as shown). For other guns, you may want a different arrangement. But in each case you want to use your empty cartridge case to draw the position of the circles on the paper. Like so:

Also note that I have a couple of marks showing the approximate ends of the strip. You want a bit of a tab on either end, to make it easy to grab and use the strip. But the final amount (and whether square or rounded off) is entirely up to your preference.

Position the template and vinyl for punching. Here I recommend that you use either a piece of dense cardboard or a scrap piece of wood. You can tape down the template if you want. But position the template, then lay the strip of vinyl on top of it in alignment with the template.

Heat up the case and/or strip. Again, the source of the heat really won’t matter. It can be a heat gun. Or a warm brick. Or a hair dryer. Whatever you have handy. Now, this may not be necessary. With some vinyls, you don’t need to really heat them up. But I have found that it makes things easier if you do, as the vinyl becomes softer and more pliable. And you can see in the image above that I have a .38sp case positioned in front of a heat gun, to make it even easier.

Position the case and strike with a hammer. If you have heated up the case, or if you’re worried about smacking your fingers with the hammer, the easy thing to do is to pick up the case with a common pair of pliers and then hold it in position. Put the mouth of the case over the vinyl/template in the correct position, then hit the case with the hammer.

How hard to hit, or how many times, will depend. But ideally, you want to have the case punch through the vinyl in a clean and complete way, so you have a small disk of removed vinyl left. This is the advantage of using the case instead of trying to cut the vinyl with a knife or drill bit: you wind up with a good clean cut the *exact* size of the cartridge.

Repeat as many times as necessary. Until you have all the holes punched out.

Then trim the strip as desired. Once done, insert loaded cartridges and it’s ready to use.

That’s it!

I thought about patenting this idea, or seeing if I could sell it to some manufacturer. But it seemed like a good thing to just share as an ‘open source’ idea with the firearms/self-defense community so it could be used widely. If you found this instructional post useful in making your own customized speed strips, and would like to contribute a couple of bucks, just send a PayPal donation here: jimd@ballisticsbytheinch.com Proceeds will be shared with Grant Cunningham, who inspired this design.

Jim Downey

Handgun caliber and lethality.

This post is NOT about gun control, even though the article which it references specifically is. I don’t want to get into that discussion here, and will delete any comments which attempt to discuss it.

Rather, I want to look at the article in order to better understand ‘real world’ handgun effectiveness, in terms of the article’s conclusions. Specifically, as relates to the correlation between handgun power (what they call ‘caliber’) and lethality.

First, I want to note that the article assumes that there is a direct relationship between caliber and power, but the terminology used to distinguish between small, medium, and large caliber firearms is imprecise and potentially misleading. Here are the classifications from the beginning of the article:

These 367 cases were divided into 3 groups by caliber: small (.22, .25, and .32), medium (.38, .380, and 9 mm), or large (.357 magnum, .40, .44 magnum, .45, 10 mm, and 7.62 × 39 mm).

And then again later:

In all analyses, caliber was coded as either small (.22, .25, and .32), medium (.38, .380, and 9 mm), or large (.357 magnum, .40, .44 magnum, .45, 10 mm, and 7.62 × 39 mm).

OK, obviously, what they actually mean are cartridges, not calibers. That’s because while there is a real difference in average power between .38 Special, .380 ACP, 9mm, and .357 Magnum cartridges, all four are nominally the same caliber (.355 – .357). The case dimensions, and the amount/type of gunpowder in it, makes a very big difference in the amount of power (muzzle energy) generated.

So suppose that what they actually mean is that the amount of power generated by a given cartridge correlates to the lethality of the handgun in practical use. Because otherwise, you’d have to include the .357 Magnum data with the “medium” calibers. Does that make sense?

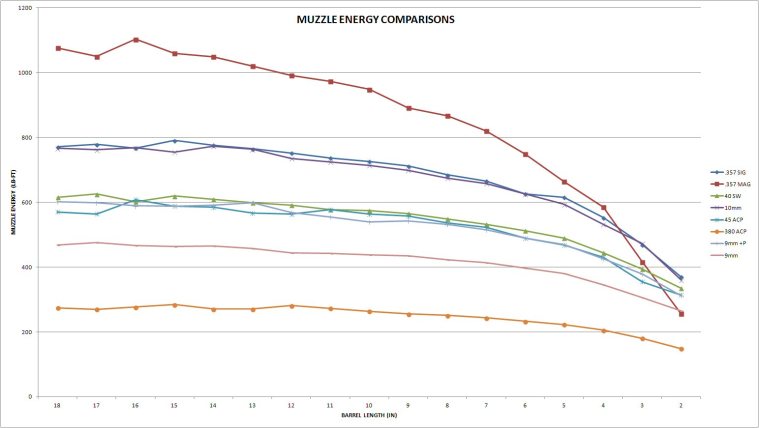

Well, intuitively, it does. I think most experienced firearms users would agree that in general, a more powerful gun is more effective for self defense (or for offense, which this study is about). Other things being equal (ability to shoot either cartridge well and accurately, concealability, etc), most of us would rather have a .38 Sp/9mm over a .22. But when you start looking at the range of what they call “medium” and “large” calibers, things aren’t nearly so clear. To borrow from a previous post, this graph shows that the muzzle energies between 9mm+P, .40 S&W, and .45 ACP are almost identical in our testing:

Note that 10mm (and .357 Sig) are another step up in power, and that .357 Mag out of a longer barrel outperforms all of them. This graph doesn’t show it, but .38 Sp is very similar to 9mm, .45 Super is as good as or better than .357 Mag, and .44 Magnum beats everything.

So, what to make of all this? This claim:

Relative to shootings involving small-caliber firearms (reference category), the odds of death if the gun was large caliber were 4.5 times higher (OR, 4.54; 95% CI, 2.37-8.70; P < .001) and, if medium caliber, 2.3 times higher (OR, 2.25; 95% CI, 1.37-3.70; P = .001).

certainly seems to carry a lot of import, but I’m just not sure how much to trust it. My statistical skills are not up to critiquing their analysis or offering my own assessment using their data in any rigorous way. Perhaps someone else can do so.

I suspect that what we actually see here is that there is a continuum over a range of different handgun powers and lethality which includes a number of different factors, but which the study tried to simplify using artificial distinctions for their own purposes.

Which basically takes us back to what gun owners have known and argued about for decades: there are just too many factors to say that a given cartridge/caliber is better than another in some ideal sense, and that each person has to find the right balance which makes sense for themselves in a given context. For some situations, you want a bigger bullet. For other situations, you want a smaller gun. And for most situations, you want what you prefer.

Jim Downey

Reprise: the *other* perfect concealed carry revolver(s).

Prompted by my friends over at the Liberal Gun Club, this is another in an occasional series of revisiting some of my old articles which had been published elsewhere over the years, perhaps lightly edited or updated with my current thoughts on the topic discussed. This is an article I wrote for Guns.com, and it originally ran 11/26/2011. Some additional observations at the end.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Smith & Wesson models 442 and 642 revolvers have their roots back more than 60 years ago. Needless to say there have been any number of variations on the J-frame theme over time (there are currently 49 versions offered on the S&W website), but perhaps the most popular has been the Airweight 642 (in stainless steel or brushed aluminum, and a variety of grips). The 642 certainly has been a very good seller, and has been at or near the top of S&W’s sales for most of the last decade. The 442 and 642 models are identical in every way except finish (the 442 is blued), but the 642 is more popular.

Why is this gun so popular? Well, it does everything right, at least as far as being a self-defense tool. It’s small, lightweight, hides well in a pocket or purse, is intuitively easy to shoot, and it handles the dependably potent .38 Special cartridge.

But let me expand on those points.

The first three are all tied together. For anyone who is looking for a gun to carry concealed, the J-frame size has a lot going for it. The 642’s barrel is one- and 7/8-inches. Overall length is just a bit more than six inches. Though the cylinder is wider than most semi-autos, the overall organic shape of the gun seems to make it hide better in a pocket or behind clothing. The Airweight 642 weighs just 15 ounces unloaded, and not a lot more loaded. For most people, this is lightweight enough to carry in a pocket or purse without really noticing it. Put it in a belt holster and you’ll not even know it is there.

Easy to shoot? Well, yeah, though it takes a lot of work to be really accurate with one at more than close self-defense distances. The 642 is Double Action Only (DAO), which means that the hammer is cocked and then fired all with one pull of the trigger – nothing else needs to be done. There’s no safety to fumble with. Just point and click. Almost anyone can be taught to use it with adequate accuracy at self-defense distances (say seven yards) in a single trip to the range.

The modern .38 Special +P cartridge is more than adequate for “social work”. From my 642 we tested five different premium defensive loads and four of the five were between 900 and 1000 fps. Tests from Brassfetcher have shown that these cartridges both penetrate and expand well, too.

One more thing – the design of the Centennial models, with the internal hammer, means that they are snag-free. You don’t have to worry about some part of the gun catching on clothing or other items when drawing it from concealment. This can save your life.

With all the good being said, I do have two criticisms. The first one is minor, and easily fixed: the trigger. Oh, it’s good, but it could be a little bit smoother right out of the box (like Ruger’s LCR). The good news is that this can usually be worked out with just some dry-firing exercises.

The second is the front site. S&W is still offering the guns with just a simple ramp sight. They should switch over to some variety of tritium sight or fiber-optic (or combination), as they have done with many of their other J-frame models. This is one change which would help in low-light conditions.

So, there ya go. Want the nearly perfect pocket pistol? You’d be hard pressed to do better than a 642 or 442.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

There’s not a lot I would change in the seven years since I first wrote this, which in itself says a hell of a lot about the popularity of the 442/642 models. They’re still ubiquitous, high quality, and effective self-defense guns.

After that was written we did another large BBTI test which included the .38 Special cartridge, which confirmed what I already knew: that while there are indeed some better and some worse performing brands of ammo available for the snubbie, for the most part all decent ‘self-defense’ ammo performs adequately. While my friend Grant Cunningham recommends the Speer 135gr JHP Short-barrel ammo (which I used to carry and still like), I now prefer Buffalo Bore’s 158gr LSWCHP +P for my M&P 360 — I’ve repeatedly tested that ammo at 1050fps out of my gun, which gives me a muzzle energy of 386 ft-lbs. But it’s not for the recoil-shy, particularly out of a 11.4oz gun. As always, YMMV.

While S&W hasn’t changed the sight offerings on the 442/642, there are lasers available for the guns, which some people like. Personally, at the range which these guns are likely to be used, I don’t see the benefit. But if you like a laser, go for it.

Bottom line, the 442/642, like the Ruger LCR, are nearly perfect revolvers for concealed carry in either a pocket or a belt holster.

Jim Downey

Reprise: Is the Ruger LCR a perfect concealed carry revolver?

Prompted by my friends over at the Liberal Gun Club, this is another in an occasional series of revisiting some of my old articles which had been published elsewhere over the years, perhaps lightly edited or updated with my current thoughts on the topic discussed. This is an article I wrote for Guns.com, and it originally ran 5/3/2012. Some additional observations at the end.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Sturm, Ruger & Company line of LCR composite-frame revolvers have been available for a few years now (2009) and since expanded from the basic .38 Special that weighs 13.5 ounces, to a 17-ounce version that can handle full .357 magnum loads, and a slightly heavier one that shoots .22 Long Rifle.

Ruger makes excellent firearms and I have grown up with them, but I was more than a little skeptical at the prospect of a revolver with a composite frame when I first heard about it. And the initial images released of the gun didn’t belay my skepticism.

But then the first Ruger LCR revolvers were actually introduced and I found out more about them. The frame is actually only partly composite while the part that holds the barrel, cylinder, and receiver is all aluminum. The internal components like the springs, firing pin, trigger assembly, et cetera are all housed in the grip frame and are well supported and plenty robust. My skepticism turned to curiosity.

When I had a chance to actually handle and then shoot the LCR, my curiosity turned to enthusiasm. Since then, having shot several different guns of both the .38 Special and .357 LCR models, I have become even more impressed. Though I still think the LCR is somewhat lacking in the aesthetics department. But in the end it does what it is designed to do.

Like the S&W J-frame revolvers, the models it was meant to compete with, the LCR is an excellent self-defense tool. It’s virtually the same size as the J-frames and the weight is comparable (depending on which specific models you’re talking about). So it hides as well in a pocket or a purse because it has that same general ‘organic’ shape.

The difference is, the LCR is, if anything, even easier to shoot than your typical J-frame Double Action Only revolver (DAO, where the hammer is cocked and then fired in one pull of the trigger). I’m a big fan of the Smith & Wesson revolvers, and I like their triggers. But the LCR has a buttery smooth, easy-to-control trigger right out of the box, which is as good or better than any S&W. Good trigger control is critical with a small DAO gun and makes a world of difference for accuracy at longer distances. I would not have expected it, but the LCR is superior in this regard.

Like any snub-nosed revolver, the very short sight radius means that these guns can be difficult to shoot accurately at long distance (say out to 25 yards). But that’s not what they are designed for. They’re designed to be used at self-defense distances (say out to seven yards). And like the J-frame DAO models, even a new shooter can become proficient quickly.

I consider the .38 Special model sufficient for self defense. It will handle modern +P ammo, something quite adequate to stop a threat in the hands of a competent shooter. And the lighter weight is a bit of an advantage. But there’s a good argument to be made for having the capability to shoot either .38 Special or .357 magnum cartridges.

My only criticism of the LCR line is that they haven’t yet been around long enough to eliminate potential aging problems. All of the testing that has been done suggests that there won’t be a problem and I trust that, but only time will truly tell if they hold their value over the long haul.

So, there ya go. To paraphrase what I said about the S&W Centennial models: “Want the nearly perfect pocket gun? You’d be hard pressed to do better than a Ruger LCR.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

It’s been six years since I wrote this, which means the early versions of the LCR have now been around for almost a decade. And as far as I know, there hasn’t yet been a widespread problem with them holding up to normal, or even heavy, use. So much for that concern.

And Ruger has (wisely, I think) expanded the cartridge options for the LCR even further. You can still get the classic 5-shot .38 Special and .357 Magnum versions, as well as the 6-shot .22 Long Rifle one. But now you can also get 6-shot .22 Magnum or .327 Magnum versions, as well as a 5-shot offering in 9mm. Each cartridge offers pros and cons, of course, as well as plenty of opportunity for debate using data from BBTI. Just remember that the additional of the cylinder on a revolver effectively means you’re shooting a 3.5″ barrel gun in the snubbie model, according to our charts. Personally, I like this ammo out of a snub-nosed revolver, and have consistently chono’d it at 1050 f.p.s. (or 386 foot-pounds of energy) out of my gun.

For me, though, the most exciting addition has been the LCRx line, which offers an exposed hammer and SA/DA operation:

I like both the flexibility of operation and the aesthetics better than the original hammerless design. But that’s personal preference, nothing more.

The LCR line has also now been around long enough that there are a wide selection of accessories available, from grips to sights to holsters to whatever. Just check the Ruger Shop or your favorite firearm supply source.

So, a perfect pocket gun? Yeah, I think so. Also good for a holster, tool kit, or range gun.

Jim Downey

Reprise: When is a Magnum not really a Magnum?

Prompted by my friends over at the Liberal Gun Club, this is another in an occasional series of revisiting some of my old articles which had been published elsewhere over the years, perhaps lightly edited or updated with my current thoughts on the topic discussed. This is an article I wrote for Guns.com, and it originally ran 6/5/2013. Some additional observations at the end.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Those are all claims taken right off of the box of three different boxes of .22 Magnum (technically, the .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire cartridge) ammo. And when you see numbers like those, it’s really easy to get excited about how much more powerful the .22 Magnum is over your standard .22 LR.

But what do those numbers really mean? And can you really expect to get that kind of performance? Do you get a different kind of performance out of your rifle than you get out of your little revolver?

That’s one of the reasons that our Ballistics By The Inch project exists: to find out just exactly what the reality of handgun cartridge performance is, and to see how it varies over different lengths of barrel.

And the first weekend of May, we did a full sequence of tests of 13 different types of .22 Magnum ammo to find out.

About our tests

About four years ago we started testing handgun cartridges out of different lengths of barrel, using a Thompson/Center Encore platform, which has been altered to allow a number of different barrels to be quickly mounted. The procedure is to set up two chronographs at a set distance from a shooting rest, and fire three shots of each type of ammo, recording the results. Once we’ve tested all the ammo in a given caliber/cartridge, we chop an inch off the test barrel, dress it, and repeat the process, usually going from an 18-inch starting length down to 2 inches. The numbers are then later averaged and displayed in both table and chart form, and posted to our website for all to use.

For those who are interested in the actual raw data sets, those are available for free download. To date we’ve tested over 25,000 rounds of ammunition across 23 different cartridges/calibers.

To do the .22 Magnum tests things were slightly different. We started with a Thompson .22 “Hot Shot” barrel and had it re-chambered to .22 Magnum. Since this barrel started out 19-inches long, we included that measurement in our tests.

So, how did the .22 Magnum cartridge do?

See those claims from manufacturers at the top of this article? Two of the three were supported by our test results. The third was not.

Data sheet from the test.

I don’t want to pick on those specific brands/types of ammo, though. I just grabbed three of the boxes we tested at random. Altogether we tested 13 different brands/types of .22 Magnum ammo, and let’s just say that the performance you actually see out of your gun will probably vary from what you see claimed from a manufacturer.

Now, that’s not because the ammo manufacturers are lying about the performance of their ammo. Rather, the way they test their ammo probably means that it isn’t like how you will use their ammo. This is most likely due to the fact that the barrel length and testing conditions are pretty different than your typical “real world” gun.

So, what can you expect from a .22 Magnum cartridge?

Well, that pretty much depends on how long a barrel you have on your gun.

Most handgun cartridges show a really sharp drop-off in velocity/power out of really short barrels. Typically, going from a 2- to 3-inch barrel makes a bigger difference than going from a 3- to 4-inch barrel.

Also typically, most handgun cartridges tend to level out somewhere around 6 to 8 inches. Oh, they usually gain a bit more for each inch of barrel after that, but the increase each time is increasingly small.

The real exception to this, as I have noted previously, are the “magnum” cartridges: .327 Magnum, .357 Magnum, .41 Magnum and .44 Magnum. The velocity/power curves for all these tend to climb longer, and show more gain, all the way out to 16 to 18 inches or more. There are exceptions to all these rules, but the trends are pretty clear.

So, does the .22 Mag deserve to be listed with the other magnum cartridges?

Well — maybe. Compared to the .22 LR, the .22 Magnum gains more velocity/power over a longer curve. But it also starts to flatten out sooner than the other magnums — usually at about 10 to 12 inches. Like most handgun cartridges, there are gains beyond that, but they tend to be smaller and smaller.

Bottom line

For me, the take-away lesson from these tests is that the .22 Magnum is a cartridge that is best served out of rifle barrel, even a short-barreled rifle. At the high end we were seeing velocities that were about 50 percent greater than what you’d get out of a similar weight bullet from a .22 LR. In terms of muzzle energy, there’s an even bigger difference: 100 percent or more power in the .22 Magnum over the .22 LR.

But when you compare the two on the low end, out of very short barrels, there’s very little if any difference: about 10 percent more velocity, perhaps 15 percent more power. What you do notice on the low end is a lot more muzzle flash from the .22 Magnum over .22 LR.

As you can see, there’s not a whole lot of rifling past the end of the cartridge when you get *that* short.

While you do see a real drop-off in velocity for the other magnums from very short barrels, they tend to start at a much higher level. Compare the .357 Magnum to the .38 Special, for example, where the velocity difference is 30 to 40 percent out of a 2-inch barrel for similar weight bullets, with a muzzle energy difference approaching 100 percent. Sure, you get a lot of noise and flash out of a .357 snubbie, but you also gain a lot of power over a .38.

But then there’s the curious case of the Rossi Circuit Judge with an 18.5-inch barrel, chambered in .22 Magnum. You see, it only performed as well as my SAA revolver with the 4.625-inch barrel. This was so completely unexpected that we thought we had to have made a mistake, or the chronos were malfunctioning, or something. So we went back and tested other guns for comparison. Nope, everything was just fine, and the other guns tested as expected.

So we made a closer examination of the Rossi and it just goes to show where there’s a rule, there’s an exception. Yup, there’s a good reason why it was giving us the readings it was. And I’ll reveal why when I do a formal review of that gun.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

OK, first thing I want to say: the reason the Circuit Judge performed so poorly was that it had a forcing cone the size of a .357 magnum on it, either allowing far too much gas to escape as the bullet made the transition from the cylinder to the barrel or because the chamber was so badly out of alignment with the barrel that it was necessary for the bullet to be guided into the barrel by first striking the side of the cone. Either way, it was a problem.

Next thing: since I wrote this 4+ years ago, I have seen countless examples of people insisting that even a little NAA .22mag pistol is MUCH more powerful than the .22lr version.

No, the .22mag is not more powerful at those very short barrel lengths. It isn’t until you get to 5 – 6″ that the .22mag starts to really outperform the .22lr. Take a look at the Muzzle Energy charts yourself:

This is not to dis the .22mag. It’s a fine cartridge — in the right application. For me, that means out of a rifle. And there are good reasons to have a handgun chambered in .22mag, such as ammo compatibility with a rifle or just flexibility in ammo availability in the case of a convertible revolver like the one I have. Just understand what the real advantages and disadvantages actually are before you make a decision.

Jim Downey

Reprise + New Review: Uberti Lightning and Taurus Thunderbolt pump carbines.

Prompted by my friends over at the Liberal Gun Club, this is another in an occasional series of revisiting some of my old articles which had been published elsewhere over the years, lightly edited or updated with my current thoughts on the topic discussed. This is an article I wrote for Guns.com, and it originally ran 2/27/2012. In addition, I am including a new but related review of the Taurus Thunderbolt following the original review.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I have owned several lever guns over the years—a style I deeply enjoy. Currently, I have a Winchester 94AE in .44 magnum, which I love. However, I always keep my eyes open for a lever gun in .357 mag. It’s a cartridge that really begins to shine when paired with a carbine length barrel. Based on BBTI testing, it gains upwards of 50 percent velocity and pushes 1,200 foot/pounds of muzzle energy. But then the Uberti Lightning came into my life—a .357 pump carbine—and I wasn’t quite sure how to feel.

Don’t Forget Where You Come From

It’s a reproduction of the original Colt Lightning, originally manufactured in 1884 (but, curiously, listed as the Model 1875 by Uberti), and a pretty faithful reproduction at that. The only changes it has are to meet modern safety demands. Specifically, there’s a new hammer safety (of the transfer-bar variety), which eliminates the option to fire the gun just by pumping new rounds while keeping the trigger pulled. This also greatly reduces the chance of an accidental discharge.

The Uberti Lightning I shot was the ‘short rifle’ version, meaning it has a 20-inch barrel, with a case-hardened frame and trigger guard. It’s a very attractive gun with a top-notch fit and finish, a beautiful walnut stock—smooth in back and checkered on the slide—and good detail work. The case-hardening is quite attractive, but the gun is available in just a blued version if you prefer.

When first loading the gun I experienced a common problem that Uberti cautions about (and something I was warned about by several other reviewers): it is relatively easy to get a cartridge wedged under the carrier that loads a round from the tubular magazine into the chamber. This can also happen when you cycle the gun, if you’re not careful to push the slide grip fully forward and fully back. I wasn’t the only one of the three of us trying the gun who had this problem, and each time we had to stop, dislodge the cartridge with a small screwdriver, then cycle the action fully.

It’s a flaw in the design, there’s little doubt about that. However, once we all got the hang of it, we had no problems firing the gun quickly and accurately.

And I think that is the nicest thing about the Lightning: once you learn how to use it, it is faster and easier to stay on target than using a lever gun, at least for me. And I have a fair amount of experience shooting lever guns. You can run through 10 rounds almost as fast as you can pull the trigger.

Shooting

The gun shot well, and was very accurate. At 25 yards (the longest distance we had available) it was no challenge to keep rounds in the X. Others have reported that it is just as accurate out to 50 yards, and I have no difficulty believing that.

Recoil is minimal, even with ‘full house’ 158 grain loads. The gun does have a curved metal buttplate, so the recoil-sensitive shooter could easily add something there to cushion recoil if necessary.

The gun is built robustly enough that it should handle just about any .357 magnum load out there without excess wear, and of course you can shoot .38 specials if you’re looking at reduced power needs or want to save a little coin at the range.

Conclusion

The Uberti website no longer lists the Lightning as available for sale, so if you’re interested in one of these guns you’ll need to hunt for it on your favorite firearms auction/sale site. The MSRP was $1259 last I saw.

So, if like me you’ve been thinking that you need to get a .357 lever gun, broaden your horizons a bit and consider the Uberti Lightning pump, instead. I am.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

And about a year ago, I found one. Well, kinda.

What I found was a Taurus Thunderbolt:

That’s a 26″ barrel, and the tube mag holds 14 rounds of .357 mag (I think it’ll hold 15 of .38 special, but I would have to double-check that). Stainless steel, with walnut stock and fore-grip. The MSRP was $705, and I got mine (new, unfired, but it had been a display model for Taurus, so it had been factory reconditioned) for about 2/3 that price. You can still find them on various auction/sales sites for about $600 and up.

The Taurus isn’t as nice as the Uberti was, in terms of the finish. Still, it’s quite nice enough, and the mechanical aspects all seem to be fine. Particularly after breaking it in (say 3-400 rounds), there’s much less tendency for the design flaw mentioned above to trip you up, and most of the people who have shot mine have gotten the hang of it quite quickly.

It really is a slick-shooting gun, and once you’re used to it you can fire the thing almost as fast as a semi-auto carbine. It’s also easy to keep the gun shouldered and on-target, which I find difficult to do with a lever-action gun. I’ve found the gun to be quite accurate, easily as good as the Uberti version.

Being able to ‘top off’ the tube mag is nice, and there’s no need to fuss with magazines — though reloading it is definitely slower, and an acquired skill. Also, you have to carry loose rounds in a pouch or pocket.

My Thunderbolt weighs more than the Lightning (8+ pounds compared to less than 6 for the Lightning), due to the 6″ longer barrel/magazine. That makes recoil even more manageable, and I haven’t had anyone complain about shooting it even with hot .357 magnum loads. With mild .38 special loads it’s like shooting a .22, and a lot of fun for plinking.

I’m really happy I found this gun, and again I find myself saying what I did in my original review six years ago: if you’re in the market for a lever-gun in .357 mag, consider opting for a pump version, instead. And definitely, if you get a chance to shoot either of these guns, take it. You’ll be glad you did.

Jim Downey

Reprise: Review of the finest revolver ever made — the Colt Python

Prompted by my friends over at the Liberal Gun Club, this is another in an occasional series of revisiting some of my old articles which had been published elsewhere over the years, perhaps lightly edited or updated with my current thoughts on the topic discussed. This is an article I wrote for Guns.com, and it originally ran 1/12/2012. Some additional observations at the end.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Who in their right mind would pay $1,200 . . . $1,500 . . . $2,000 . . . or more for a used production revolver? Lots of people – if it is a Colt Python.

There’s a reason for this. The Colt Python may have been a production revolver, but it was arguably the finest revolver ever made, and had more than a little hand-fitting and tender loving care from craftsmen at the height of their skill in the Colt Custom Shop.

OK, I will admit it – I’m a Python fanboy. I own one with a six-inch barrel, which was made in the early 1980s. And I fell in love with these guns the first time I shot one, back in the early 1970s. That’s my bias. Here’s my gun:

But the Python has generally been considered exceptional by shooters, collectors, and writers for at least a generation. Introduced in 1955, it was intended from the start to be a premium revolver – the top of the line for Colt. Initially designed to be a .38 Special target revolver, Colt decided instead to chamber it for the .357 Magnum cartridge, and history was made.

What is exceptional about the Python? A number of different factors.

First is the look of the gun. Offered originally in what Colt called Royal Blue and nickel plating (later replaced by a polished stainless steel), the finish was incredible. The bluing was very deep and rich, and still holds a luster on guns 40 to 50 years old. The nickel plating was brilliant and durable, much more so than most guns of that era. The vent rib on top of the barrel, as well as the full-lug under, gave the Python a distinctive look (as well as contributing to the stability of shooting the gun). It had excellent target sights, pinned in front (but adjustable) and fully adjustable in the rear.

The accuracy of the Python was due to a number of factors. The barrel was bored with a very slight taper towards the muzzle, which helped add to accuracy. The way the cylinder locks up on a (properly functioning) Python meant that there was no ‘play’ in the relationship between the chamber and the barrel. The additional weight of the Python (it was built on a .41 Magnum frame for strength) helped tame recoil. And the trigger was phenomenally smooth in either double or single action. Seriously, the trigger is like butter, with no staging or roughness whatsoever – it is so good that this is frequently the thing that people remember most about shooting a Python.

The Python had minimal changes through the entire production run (it was discontinued effectively in 1999, though some custom guns were sold into this century). It was primarily offered in four barrel lengths: 2.5-, 4-, 6-, and 8-inch, though there were some special productions runs with a three-inch barrel. Likewise, it was primarily chambered in .357 Magnum, though there were some special runs made in .38 Special and .22 Long Rifle.

The original grips were checkered walnut. Later models had Pachmayr rubber grips. Custom grips are widely available, and very common on used Pythons (such as the cocobolo grips seen on mine).

The Python was not universally praised. The flip side of the cylinder lock-up mechanism was that it would wear and get slightly out-of-time (where the chamber alignment was no longer perfect), necessitating gunsmith work. Mine needs this treatment, and I need to ship it off to Colt to have the work done. And the high level of hand-finishing meant that the Python was always expensive, and the reason why Colt eventually discontinued the line.

If you have never had a chance to handle or shoot a Python, and the opportunity ever presents itself, jump on it. Seriously. There are very few guns that I think measure up to the Python, and here I include even most of the mostly- or fully-custom guns I have had the pleasure of shooting. It really is a gun from a different era, a manifestation of what is possible when craftsmanship and quality are given highest priority. After you’ve had a chance to try one of these guns, I think you’ll begin to understand why they have held their value to a seemingly irrational degree.

On average, for online gun sellers, the Colt Python sells for more than $2,000, but there are occasions where you’ll find it for less than a grand.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The value of the Pythons has continued to rise in the almost six years since I wrote that, and I’m just glad I got it before the market went nuts. I haven’t seen one sell for less than a thousand bucks in years.

I did send my Python off to Colt to have it re-timed before the last of the smiths who had originally worked on the guns retired, and it came back in wonderful condition. I don’t know what all they did to it, but it cost me a ridiculously modest amount of money — like under $100. It was clear that there was still a lot of pride in that product.

Whenever I get together with a group of people to do some shooting, I usually take the Python along and encourage people to give it a try. More than a few folks have told me that it was one of their “Firearms bucket list” items, and I have been happy to give them a chance to check it off. Because, really, everyone who appreciates firearms should have a chance to shoot one of these guns at some point in their lives — it’d be a shame to just leave such a gun in the safe.

Jim Downey

Reprise: Bond Arms Derringer review.

Prompted by my friends over at the Liberal Gun Club, this is another in an occasional series of revisiting some of my old articles which had been published elsewhere over the years, perhaps lightly edited or updated with my current thoughts on the topic discussed. This is an article I wrote for Guns.com about six years ago, and it originally ran without a byline as an “Editor’s Review” for all the different Bond Arms Derringers. Images used are from that original article. Some additional observations at the end.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Is there anything more classically American than a derringer?

Yeah, sure there is. Sam Colt’s revolver, JMB’s M1911, the lever-action repeating rifle — the list goes on. We’ve got a long and admirable history in firearms design, but derringers remain one of the most easily identifiable and storied handguns even among those who know very little about firearms. Anyone who has seen any Western has probably seen a derringer of one sort or another and recognized it as such.

So it’s unsurprising that there remains a pretty solid interest in derringers, even in this day and age of smaller and lighter handguns that are arguably “better” for the role that derringers originally filled as a pocket/backup gun.

Since the mid 1990s Bond Arms has been producing fine-quality derringers based on the original nineteenth century iconic Remington design. I own a Bond C2K model chambered in .410/.45 Colt. The 3.5″ barrel will handle up to 3″ long .410 shotgun shells, or the .45 Colt ammunition of your choice. In addition, I’ve had the good fortune to shoot just about every other barrel configuration that Bond makes for this firearm (because the barrels are easily interchangeable). My C2K has the standard sized Rosewood grips – though they can be swapped out for extended grips with very little difficulty.

It is a very well made and attractive little gun. The fit and finish are excellent. The brushed stainless steel finish wears well and is resistant to marring. Modern design tweaks include a trigger guard and a crossbolt safety, but both of these are well integrated with the overall appearance. There is sufficient weight to moderate the recoil of even the most powerful loads. I like the gun — a lot — for what it is: something of a novelty item suitable for certain tasks.

Those tasks?

Well, having a bit of fun, mostly, and with the appropriate .410 load it’d make a decent gun for snakes. That’s about it — I’m one of those who think that it isn’t very well suited for concealed-carry purposes given the weight and the two-shot capacity.

There are some things I really like. It is smaller than a J-frame sized revolver, is very comparable to any of the common “micro .380″ guns in overall size, and can pack a much more powerful cartridge depending on your barrel choice.

Features

However, there are also a few things I don’t much care for with this gun. Trigger pull can be very erratic from one gun to the next — some I have shot are very easy and smooth, but the one I have is so hard that my wife could not fire it reliably. I haven’t taken the time to investigate what would be involved in easing and smoothing out the trigger pull, but this is something that shouldn’t be necessary for the owner to have to fuss with.

Accuracy isn’t great, even considering what it was meant to be. This is more of a problem with my particular model since there is only 0.5″ of rifling at the end of the barrel, in order to accommodate a 3″ shot shell. If I wanted to use this gun for, say, SASS competition, I’d probably get a .38 special/.357 magnum barrel for it and be much happier with the accuracy.

The Verdict

So, there you go. If you shoot Cowboy Action, this’d be a fun little gun to include in your set-up. If you’re worried about snakes while out fishing or hiking, a Bond derringer would be a good solution. Or, if you just want to have a dependable version of a classic American novelty item, this is a great option.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

First things first: I discovered a year or so after that was posted that the common wisdom about the triggers was to remove the trigger guard. It’s easily done with just an Allen wrench, and makes all the difference in the world, because the trick to the trigger is to get your finger very low on the trigger to have proper leverage. Since the gun is single-action only, removing the trigger guard doesn’t present any safety problems.

Also, I have indeed expanded my selection of barrels for the Bond and now have both the .38/.357 barrel and a .45 acp barrel. Shooting full magnums (or .45 Super) out of the derringer isn’t fun, but does give you much more power options. And as I expected, accuracy with these barrels is much better than with the .410/.45 Colt barrel.

I still think that there are better options for a small concealed-carry/backup gun. But particularly with the right ammo, the Bond Arms derringer isn’t a bad choice. YMMV, of course.

Jim Downey

Reprise: Levering the Playing Field: a Magnum Opus

Prompted by my friends over at the Liberal Gun Club, this is another in an occasional series of revisiting some of my old articles which had been published elsewhere over the years, perhaps lightly edited or updated with my current thoughts on the topic discussed. This is an article I wrote for Guns.com, and it originally ran 3/26/2011. Some additional observations at the end.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In an earlier article, when I said you’d get about a 15% increase in bullet velocity when using a pistol caliber carbine over a handgun, I lied.

Or, rather, I was neglecting one particular class of pistol ammunition which can develop upwards of a 50% increase in velocity/power in a carbine over a handgun: the “magnums,” usually shot out of a lever-action gun. This would include .327 Federal Magnum, .357 Magnum, .41 Magnum, and .44 Magnum.

These cartridges are rimmed, initially developed as powerful handgun rounds, and have their origins in black powder cartridges. This history is important for understanding why they are different than most of the other pistol cartridges and the carbines that use them.

We’ll start with the .357 Magnum, the first of these cartridges developed.

Back in the 1930s a number of people, Elmer Keith most notable among them, were looking to improve the ballistic performance of the .38 Special cartridge. This had been a cartridge originally loaded with black powder. Black powder takes up a lot of space – typically two to four times as much space as smokeless powder of a similar power. Meaning that when people started loading .38 Special cartridges with smokeless powder, the cartridge was mostly empty.

Now, if you were looking to get more power out of a .38 Special, and you saw all that unused space in the cartridge, what would be the obvious thing to do? Right – add more smokeless powder.

The problem is, many of the handguns chambered for the .38 Special using black powder were not strong enough to handle .38 Special cartridges over-charged with smokeless powder. And having handguns blowing up is rough on the customers. Heavier-framed guns could handle the extra power, but how to distinguish between the different power levels and what cartridge was appropriate for which guns?

The solution was to come up with a cartridge, which was almost the same as the .38 Special, but would not chamber in the older guns because it was just a little bit longer. This was the .357 Magnum.

There are two important aspects of the cartridge as far as it applies to lever guns. One is just simply the ability to use more gunpowder (a typical gunpowder load for a .357 magnum uses about half again as much as used in a .38 Special.) And the other is that you can get more complete combustion of the gunpowder used, perhaps even use a much slower burning gunpowder. This means that the acceleration of the bullet continues for a longer period of time.

How much of a difference does this make? Well, from the BBTI data for the .357 Magnum, the Cor Bon 125gr JHP out of a 4″ barrel gives 1,496 fps – and 2,113 fps out of an 18″ barrel. Compare that to the .38 Special Cor Bon 125gr JHP out of a 4″ barrel at 996 fps and 1,190 fps out of an 18″ barrel. That’s a gain of 617 fps for the .357 Magnum and just 194 fps for the .38 Special. Put another way, you get over a 41% improvement with the Magnum and just 19% with the Special using the longer barrel.

Similar improvements can be seen with other loads in the .357 Magnum. And with the other magnum cartridges. And when you start getting any of these bullets up in the range of 1,500 – 2,000 fps, you’re hitting rifle cartridge velocity and power. The low end of rifle cartridge velocity and power, but nonetheless still very impressive.

There’s another advantage to these pistol caliber lever guns: flexibility. Let’s take that .357 again. On the high end of the power band, you can use it as a reliable deer-hunting gun without concern. But if you put some down-loaded .38 Special rounds in it, you can also use it to hunt rabbit or squirrel. I suppose you could even use snake/rat shot loads, though most folks don’t recommend those loads due to concerns over barrel damage. Shooting mild .38 Special loads makes for a great day just plinking at the range.

One thing that I consider a real shame: you can get good quality lever guns for the .357, the .41, and the .44 magnums. But to the best of my knowledge, no one yet makes a .327 Magnum lever gun. I would think that such a gun would meet with a lot of popularity – properly designed, it should be able to handle the .327 Federal Magnum cartridge, the .32 H&R cartridge, even the .32 S&W Long. Again, with the right powder loads, this would give the gun a great deal of flexibility for target shooting and hunting small to medium sized game/varmits.

So, if you like the idea of having a carbine in the same cartridge as your handgun, but want to be able to maximize the power available to you, think about a good lever gun. It was a good idea in the 19th century, and one that still makes a lot of sense today.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Some additional thoughts …

I’m still a little surprised that no manufacturer has come out with a production .327 mag lever gun, though occasionally you hear rumors that this company or that company is going to do so. But I must admit that as time has gone on I’ve grown less interested in the .327 cartridge, since firearms options are so limited — definitely a chicken & egg problem.

One very notable absence from the above discussion is the .22 WMR (.22 Magnum), for the simple reason that we hadn’t tested it yet when I wrote the article. You can find a later article about it here.

Something I didn’t address when I wrote the article initially was ammunition which was formulated to take greater advantage of the longer barrel of a lever gun. Several manufacturers produce such ammo, perhaps most notably Hornady and Buffalo Bore. A blog post which includes the latter ammo out of my 94 Winchester AE can be found here, with subsequent posts here and here.

And lastly, there’s another cartridge we tested which really should be included in the “magnum” category, because it sees the same increasing power levels out to at least 18″ of barrel: .45 Super. This proved to be more than a little surprising, since it is based on the .45 ACP cartridge. Most semi-auto firearms which shoot the .45 ACP should be able to handle a limited amount of .45 Super, but if you want a lever gun set up to handle the cartridge you’ll have to get it from a gunsmith.

Jim Downey

Join the party.

All along, we’ve said that if someone wanted to take the time, trouble, and expense to do some additional research along the lines of our protocols, that we’d be happy to include their data on our site. This is particularly true if it helped expand the selection of “real world guns” associated with the data for a given caliber/cartridge. Well, for the first time someone has expressed an interest in doing just that, prompting us to come up with an outline of what standards we feel are required for making sure it relates to our previous tests.

The biggest problem is that ammo manufacturers may, and do, change the performance of their products from time to time. This is why we have on occasion revisited certain cartridges, doing full formal chop tests in order to check how specific lines of ammo have changed. That gives us a benchmark to compare other ammo after a period of several years have passed, and shows how new tests relate to the old data.

But without going to such an extent, how can we be reasonably sure that new data collected by others using their own firearms is useful in comparison to our published data?

After some discussion, we feel that so long as any new testing includes three or more of the specific types of ammo (same manufacturer, same bullet weight & design) we had tested previously, then that will give enough of a benchmark for fair comparison. (Obviously, in instances where we didn’t test that many different types of ammo in a given cartridge, adjustments would need to be made). With that in mind, here are the protocols we would require in order to include new data on our site (with full credit to the persons conducting the tests, of course):

- Full description and images of the test platform (firearm) used in the tests. This must specify the make, model number, barrel length, and condition of the firearm. Ideally, it will also include the age of the firearm.

- That a good commercial chronograph be used. Brand isn’t critical — there seems to be sufficient consistency between different models that this isn’t a concern. However, the brand and model should be noted.

- Chronographs must be positioned approximately 15 feet in front of the muzzle of the firearm used to test the ammo. This is what we started with in our tests, and have maintained as our standard through all the tests.

- That five or six data points be collected for each type of ammo tested. This can be done the way we did it, shooting three shots through two different chronographs, or by shooting six shots through one chronograph.

- All data must be documented with images of the raw data sheets. Feel free to use the same template we used in our tests, or come up with your own.

- Images of each actual box of ammo used in the test must be provided, which show the brand, caliber/cartridge, and bullet weight. Also including manufacturer’s lot number would be preferred, but isn’t always possible.

- A note about weather conditions at the time of the test and approximate elevation of the test site above sea level should be included.

We hope that this will allow others to help contribute to our published data, while still maintaining confidence in the *value* of that data. Please, if you are interested in conducting your own tests, contact us in advance just so we can go over any questions.

Jim Downey

An absurd comparison. Or is it?

We had another of those wonderful & rare mid-50s January days here today, so I decided to get out for a little range time.

In addition to the other shooting I did (basically, practice with some of my preferred CCW guns), I also did a little head-to-head comparison between a Smith & Wesson M&P 360 J-frame in .38 Special and a Colt Anaconda in .44 Magnum.

Wait … what? Why on Earth would anyone even consider trying to do such an absurd comparison? The S&W is a very small gun, and weighs just 13.3 ounces. The Anaconda is a monster, weighing in at 53 ounces (with the 6″ barrel that mine has), and is literally twice as long and high as the J-frame. The .38 Special is generally considered a sufficient but low-power cartridge for self defense, while the .44 Magnum still holds a place in the popular mind as ‘the most powerful handgun in the world‘ (even though it isn’t).

Well, I was curious about the perceived recoil between the two, shooting my preferred loads for each. The topic had come up in chatting with a friend recently, and I thought I would do a little informal test, just to see what I thought.

So for the M&P 360 I shot the Buffalo Bore .38 special +P, 158 gr. LSWHC-GC which I have chrono’d out of this gun at 1050 fps, with a ME of 386 ft-lbs.

And for the Anaconda I shot Hornady .44 Remington Magnum 240gr XTP JHP, which I have chrono’d at 1376 fps, with a ME of 1009 ft-lbs. (Actually, I don’t have a ‘preferred carry ammo’ for this gun, but this is typical of what I shoot out of it. Were I going to use it as a bear-defense gun, I’d load it with this.)

My conclusion? That the M&P 360 was worse, in terms of perceived recoil. In fact, I’d say that it was *much* worse.

It’s completely subjective, but it does make sense, for a couple of reasons.

First, look at the weight of each gun, compared to the ME of the bullets shot. The J-frame is 13.3 ounces, or about 25% of the 53 ounce weight of the Anaconda. But the ME of 386 ft-lbs of the .38 Special bullet is 38.25% of the ME of the .44 Mag at 1009 ft-lbs. Put another way, the J-frame has to deal with 29 ft-lbs of energy per ounce of the gun, where the Anaconda has just 19 ft-lbs of energy per ounce of the gun. That’s a big difference.

Also, all that recoil of the J-frame is concentrated into a much smaller grip, when compared to the relatively large grip of the Anaconda. Simply, it the difference between being smacked with a hammer and a bag of sand, in terms of how it feels to your (or at least, my) hand.

Thoughts?

Jim Downey

The illusion of precision.

Got an email which is another aspect of the problem I wrote about recently. The author was asking that we get more fine-grained in our data, by making measurements of barrel lengths by one-eighth and one-quarter inch increments. Here’s a couple of relevant excerpts:

what more is really needed, is barrel lengths between 1-7/8 and 4-1/2″.

because of the proliferation of CCW and pocket pistols, and unresolved

questions about short barrel lengths that go all over between 2 and 3.75″,

and snubby revolvers that may be even shorter.* * *

with that amount of precision, not only would you have data covering all

lengths of short barrels, but you could fabricate mathematical curves that

would predict velocities for any possible barrel length, metric or

otherwise, given the particular ammo.

It’s not an unreasonable thought, on the surface. Our data clearly shows that the largest gains in bullet velocity always come in length increases of very short barrels for all cartridges/calibers. So why not document the changes between, say, a 4.48″ barrel and a 4.01″ one? That’s the actual difference between a Glock 17 and a Glock 19, both very popular guns which are in 9mm. Or between a S&W Model 60 with a 2.125″ barrel and a S&W Model 360PD with a 1.875″ barrel?

Ideally, it’d be great to know whether that half or quarter inch difference was really worth it, when taking into consideration all the other factors in choosing a personal defense handgun.

The problem is that there are just too many different variables which factor into trying to get really reliable information on that scale.

Oh, if we wanted to, we could do these kinds of tests, and come up with some precise numbers, and publish those numbers. But it would be the illusion of precision, not actually useful data. That’s because of the limits of what we can accurately measure and trust, as well as the normal variations which occur in the manufacturing process … of the guns tested; of the ammunition used; of the chronograph doing the measurements; even, yes, changes in ambient temperature and barometric pressure.

That’s because while modern manufacturing is generally very, very good, nothing is perfect. Changes in tolerance in making barrels can lead to variation from one gun to the next. Changes in tolerance in measuring the amount of gunpowder which goes into each cartridge (as well as how tight the crimp is, or even tweaks in making the gunpowder itself) mean that no two batches of ammunition are exactly alike. And variations in making chronographs — from the sensors used, to slight differences in positioning, to glitches in the software which operate them — mean that your chronograph and mine might not agree on even the velocity of a bullet they both measure.

All of those little variations add up. Sometimes they will compound a problem in measuring. Sometimes they will cancel one another out. But there’s no way to know which it is.

This is why we’ve always said to consider our data as being indicative, not definitive. Use it to get a general idea of where your given choice of firearm will perform in terms of bullet velocity. Take a look at general performance you can expect from a brand or line of ammunition. Compare how this or that particular cartridge/caliber does versus another one you are considering.

But keep in mind that there’s no one perfect combination. You’re always going to be trading off a bunch of different factors in choosing a self-defense tool.

And never, ever forget that what matters most — FAR AND ABOVE your choice of gun or ammunition — is whether or not you can use your firearm accurately and reliably when you need to. Practice and training matters much more than whether or not you get an extra 25, or 100, or even 500 fps velocity out of whatever bullet is traveling downrange. Because if you can’t reliably hit your target under stress, no amount of muzzle energy is going to do you a damn bit of good.

Jim Downey

If you want more information about how accuracy and precision can be problematic, this Wikipedia entry is a good place to start.

First date with the Boberg XR45-S

Over the weekend I posted about picking up my new Boberg XR45-S. This afternoon I took it out for a first “getting to know you” session. More about that in a moment.

First, I want to share a couple of things I discovered in getting the Boberg out of the box, taken apart, and cleaned. This wasn’t strictly necessary, of course, because it came from the factory properly cleaned and lubed. But I’m very much a hands-on learner, and wanted to see what I was dealing with.

The gun is very user-friendly. To take it down for field stripping, you just rack the slide back, turn a lever, then move the slide forward. You don’t need any special tools, or an extra hand, or the strength of the pure. In that sense, it is very much in the modern design, as easy as a Glock. BUT without the need to dry-fire the gun first (which always makes me twitch, and may be the only thing I really dislike about the Glock design.)

Once the slide comes away from the frame, there are only 4 parts which come apart (other than the slide itself). There are no little fiddly bits to get lost or to spring out of sight when you’re not looking. You don’t have to disassemble the gun in a paper bag so that you don’t lose anything. It’s easy, obvious, and once you’ve done it following the owner’s manual, I doubt you’ll ever need to refer to the manual again. You can’t ask for more than that.

So, dis-assembly, cleaning, and re-assembly is all a breeze. Nice!

Having done so, I went through my box of misc. holsters to see what the Boberg might fit into. Because the XR45 is so new there are damned few holster-makers out there who have a holster listed to fit it. And I discovered something VERY interesting: the slide has almost the exact same dimensions as the Glock 21 (and similar Glock models). I first found this out in trying it in this little plastic holster: Glock Sport Combat Holster. I got out my calipers and did some measuring, and found that there was less than a millimeter difference in the width of the slide on the Glock 21 and the Boberg. They also have very similar profiles. And if you measure from the deepest pocket on the backstrap of either gun (where the web of your hand settles in) to the front of the trigger guard, there is less than 2 millimeters difference. Meaning that the Boberg fits almost perfectly into an open-muzzle holster for a Glock 21. Good to know!

OK, so what about going out shooting with the Boberg today?

Overall, I was very happy with how it performed on a first outing. I had a couple of minor glitches with improper feeding and ejection, but I am going to hold off on making any decisions about that until I give it at least another range session to break in. It does seem to fling spent cases somewhere into the next county, and I’m going to have to get used to that since I like to recover those cases and reload them. My very mild reloads wouldn’t cycle properly (the ones I took out are *really* mild), so I learned to take somewhat hotter loads. And the trigger is really l o n g … longer than either J-frame I own, and about like the little DAO Rohrbaugh I have. The gun seems to shoot a little to the left for me, but I won’t adjust the sights until I’m more familiar with it. Even so, I was able to consistently ding a 6″ spinner at 10 yards, which is all I expect from a pocket pistol.

How did it handle the different ammos I tried? Quite well, all in all.

I took my Glock 21 (5″ barrel) along for comparison, and shot over a single chronograph. Here are the average numbers:

Glock 21 Boberg

CorBon DPX 185gr +P 1060FPS 1030FPS

Winchester SXZ Training 230gr 850FPS 795FPS

Speer GDHP 230gr 840FPS 760FPS

CorBon JHP 230gr +P 980FPS 900FPS

The CorBon ammo is in line with what we tested formally. So that was good to see.

All together, I put about 100 rounds through the Boberg this afternoon, and wasn’t experiencing any real soreness or tiredness from all that shooting, which is unusual for such a small gun and full power loads. And just for comparison, I shot my .38Sp J-frame with 158gr LSWCHP +P from Buffalo Bore, which is my preferred SD loading for that gun, and the recoil was worse than with the Boberg. That’s for a ME comparison of 386 ft/lbs for the J-frame to 436 ft/labs for the Boberg with the 185gr CorBon loading.