Lookin’ Sharp(s).

As anyone who has read much of this blog probably knows, I (and the other BBTI guys) like weird guns. Anything that is innovative, or unusual, or uses a transitional technology, is likely to catch my eye.

One of those I got to try this past weekend is a reproduction Sharps Pepperbox. It was designed by Christian Sharps (of Sharps Rifle fame) in the middle 1800s , and proved to be a popular little hide-away gun in early .22. .30, and .32 rimfire cartridges.

In the 1960s Uberti produced a little .22short reproduction with a brass frame and plastic grips. Here’s one recently listed on Gunbroker which has an excellent description of both the reproduction and the original: Uberti Sharps Pepperbox 4 Barrel Derringer.

And here are some pics of the one we shot this weekend:

As you can see, the barrel assembly just slides forward to allow access to the breech. You put the hammer at half cock, then depress the button latch at the front of the gun, and it slides forward. Then you can drop four rounds of .22short into the barrels:

The assembly then just slides back into position, and locks. When you draw the hammer back, the firing pin (mounted on the hammer) rotates one-quarter of the way around, to strike each cartridge in turn.

Though a modern .22short has a surprising amount of energy, out of such a short barrel you’re looking at a modest 40-50 ft-lbs of muzzle energy. Would I care to be shot by one, let alone 4? Nope. And even the original loads using black powder, which would probably generate no more than about half that M.E., such a little hide-away gun would likely give a person on the other end of the barrels pause, because the risk of disability or death from infection would be significant.

Shooting the pepperbox was easy, and had no perceived recoil. Hitting a target at more than about five or six feet was another matter. Most of us tried it at about 10′, and were lucky to get one or two rounds into a 8″ circle. You might be able to improve on that with practice, but still, this was a gun meant for up close use:

It really is a cool little design, and a fun range toy. Shoot one if you ever get the chance.

Jim Downey

That takes balls.

I recently picked up a little Pedersoli Liegi Derriger kit. One of the other BBTI guys has one of these things, and I’ve always considered it a cool little piece of firearms history. Cap & ball firearms technology came along in the early part of the 1800s, supplanting flintlocks and earlier ignition systems. The Liegi design was very popular as a basic pocket/boot/muff small handgun, because it was relatively easy to load and carry, and lethal at close range.

The interesting thing about the Liegi is the loading system: you unscrew the barrel, load the powder charge in the chamber, place a round bullet on top of the powder, then screw the barrel back into place. It’s simple and fairly foolproof, and doesn’t even require a powder measure — you just fill the chamber with black powder and it’s the correct amount. Once the gun is loaded and the barrel is in place, you draw the hammer to half-cock, place a cap on the nipple, and the gun is ready. Here’s a short video showing all the steps:

In addition to doing the minor prep work on the walnut stock of the gun, I wanted to add some laser engraving on the side panels. Because it amused me, I decided to use the same basic pattern as I had used for the grips of a very modern handgun, my Customized Timberwolf G21. Here’s a pic of the finished product, and on the next page are pics of the process and comparisons to other small handguns I have:

Review: S333 Thunderstruck.

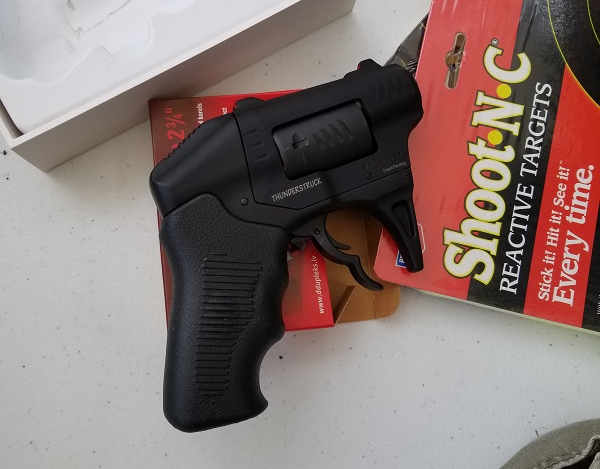

This is the Standard Manufacturing S333 Thunderstruck revolver:

It’s an innovative, 8-round revolver which fires two rounds of .22WMR (.22mag) with one pull of the trigger.

OK, if you like this not-so-little handgun, you might not want to read this review. Just move along and save yourself some time.

No, really.

If you have to think about it, here’s another pic to give you some time:

The actual S333

* * *

For those who’ve stuck around …

… good lord, don’t buy one of these things as a self/home defense gun. If you want it just because it’s kinda geeky and weird, then cool. If you want to actually use it, go spend your money on almost anything else. Seriously.

Why do I say this?

Because, for the ostensible use of the gun as a self/home defense tool, it is almost entirely unsuited. Yeah, that’s my biased opinion, on having shot the thing.

Oh, you want details? Reasons for this opinion? Fair enough.

When I first heard of it, I saw that it was .22WMR, out of a 1.25″ barrel. Now, since it is being shot out of a revolver, you can add in the length of the cylinder, and come up with an overall barrel length of about 3″.

.22WMR out of a 3″ barrel isn’t exactly useless. I mean, it beats harsh words. And, in fairness, it beats your typical .22lr. A little. You can expect about 100-110ft/lbs of energy from it. The best-performing .22lr from the same length barrel is about 90ft/lbs. Same for .25ACP.

And, if you think in terms of having two such bullets fired simultaneously, that gets you up to about 200-220ft/lbs of energy. Not impressive, but I wouldn’t want to be shot by it. I mean, it’s better than .32ACP.

Well, it would be if for one big problem: keyholing.

See, with such a very short barrel, the .22WMR bullets aren’t stabilized. They come out of the barrel, and tumble. If the bullet tumbles upon leaving the barrel, it will quickly lose energy to aerodynamic forces. And likewise, if it hits something more solid, it will also lose energy more quickly. Which will really mess up their effectiveness in penetrating deep enough into an attacker in order to be effective. Because, remember, this is supposed to be a self/home defense gun.

See for yourself:

keyholed!

Yeah, of the 8 bullets I fired (from about 5 yards, aiming at the center of the target), 7 have keyholed.

This is something that almost every review video I watched also noted. The S333 keyholes at least 50% of the time, and usually more.

So let’s go back to the comparison with .32ACP. Keyholing can happen with any caliber and almost any gun, but it tends to be rare in well-designed guns and properly matched ammunition. So, usually, you can rely on fairly consistent penetration out of .32ACP. Which, according to independent testing by Brass Fetcher, will give you 7-10″ of penetration in 20% ballistic gel. And .22WMR will do about as well.

But not if it keyholes. Which it does, out of the S333.

Now, Standard Manufacturing has said that this is something that they’re working to correct. So perhaps later versions of the gun will not have this problem.

I still wouldn’t want it. Why?

The S333 is as large and weighs (18oz) as much as many common compact 9mm semi-auto handguns. It’s larger and weighs more than most small .380 semi-auto handguns. It’s larger and weighs more than most small frame .38/.357 revolvers. Any of those alternatives offer much more potent cartridges, even in comparison to two simultaneous .22WMR rounds. And with the S333, you have four shots — your typical small revolver will be 5 or 6, and small semi-auto guns are typically 6 or more.

The S333 is also awkward and difficult to shoot. The unusual “two finger” trigger really changes how you can grip the revolver, changing how you aim and control it. It’s also a very long and very hard trigger pull — something in excess of 12 pounds, by most reports. If, like most people, you want to use a second hand to support your shooting hand (which is even more necessary when you only hold the gun with your thumb and two small fingers), about the best thing you can do is grip the wrist of the shooting hand in a modified “cup & saucer” style grip. Otherwise, the fingers of your supporting hand will be in the way of the trigger coming all the way back, which is necessary for it to fire.

Here, see what I mean with this short video of me shooting it:

I think the awkwardness of the grip and the two-finger trigger explains why most people tend to shoot the revolver high and to the right when they first encounter it. All three of us at BBTI did. Almost every review video I watched had the same thing.

I’m sure you could learn to adapt to this, and develop a secure and reliable method of shooting the gun with practice. But as a “grab it and use it” self-defense gun, it’s a problem.

One minor note while the video above is fresh in mind: did you notice the amount of flash in two of the shots? Yeah, that’s another factor of such short barrels with the .22WMR. That was while shooting it on a typical partly cloudy day in the middle of the morning. Not a major problem, but something to register.

One last thing: price. As you can see on the first pic, this particular S333 sold for $419.99, which is just under the MSRP. So while it isn’t really pricey, it isn’t cheap. In fact, it seems to be a very solid and well-made gun. The fit and finish were good. The minor problems we had with it were probably just because it was brand new (it hadn’t been fired previously). The trigger is, as noted, long and very heavy, but reasonably smooth if a little mushy. So, overall, if you wanted one of these just because it’s unique and quirky, then I think it’s a reasonably-priced gun.

But if you are looking at it as a self/home defense gun? Or even as a “back-up” for that use?

I think you have much better options.

Jim Downey

Review: Diablo 12ga double barrel pistol.

Want some fun? Get an American Gun Craft 12ga double-barrel pistol.

Want a serious self/home defense gun? Get something else.

Oops. I gave away my review’s conclusion. But you should go ahead and read the rest of this, anyway.

* * *

When one of my friends sent me a link about the new American Gun Craft 12ga double-barrel pistol, I thought it looked like a lot of fun. A lot of people thought so, and the cool little pistol got a lot of attention.

For good reason. It looked well made, well designed, and easy to use.

And it is. Check it out:

Diablo 12ga

And this is what it looks like in the hand:

Seriously, this is a very high-quality gun. It’s very solidly made. The fit & finish is impressive. The bluing is rich, deep, and lovely. The rosewood handles fit perfectly, and are warm & comfortable in the hand. They’re polished so highly I at first thought that they were plastic. The trigger is smooth, crisp, and much better than I expected.

The design is simple, but there are little things about it that are quite nice. Such as when the gun is broken open, you can rest it on any flat surface with the barrels pointing up, and it is perfectly stable for loading. If you’re shooting by yourself, this would be very handy.

Since we didn’t know what to expect, we went with the manufacturer’s recommended load of black powder to start with. That’s just 40gr of ffg, with a recommended half ounce of shot. But all we had to shoot out of the gun were 12ga balls (.69 cal ball, about 500gr — say 1.2 ounce). So we expected it to be mild shooting.

It was:

Well, according to this video, that’s probably just about 250fps, and maybe 70ft/lbs of energy. That’s about the same power as a low-performing .22 round out of a 6″ barrel. And it felt like it.

So, since the amount of lead we were shooting was more than double the recommended amount, we doubled the amount of black powder, to 80gr of ffg. Here’s that:

Well, again according to this video, that’s probably about 560fps, and maybe 340ft/lbs of energy. That’s about the same power as a typical 9mm round out of a 6″ barrel. And it felt like it. There was a bit of recoil out of the heavy pistol, but it wasn’t at all hard to manage.

Given how well the gun was made, and the mildness of the first shots, we didn’t have any qualms about increasing the amount of powder to double what was recommended. And that was a fun load to shoot. Others have pushed that boundary MUCH further, as you’ll see in either this video (referenced above) or this very long review. By using much bigger loads and different types of powder, it is possible to get up to energy levels in the range of a .357 or even .44mag out of a 6″ barrel.

So yes, it would be a pretty reliable self/home defense gun, in those terms. And we were shooting it at applicable ranges for that use, with adequate accuracy.

But consider several factors here. First, black powder is very hygroscopic: it sucks up moisture out of the air. That can be a problem with a muzzle-loading gun, and was the reason why Old West gunfighters would commonly shoot off their loads each morning and load their pistols fresh. Because wet powder can underperfom very badly. So you wouldn’t want to load the Diablo and then just set it aside for future use.

Black powder is also a slow-burning and very smoky powder. Shooting it indoors would fill the room with very acrid smoke, and may very well spew burning bits of powder out into the room, causing fires.

Lastly, while the Diablo is indeed easy to load and shoot for a black powder gun, that still takes a hell of a lot more time than it would take to load two additional cartridges into a derringer. And almost every common modern self/home defense gun offers more rounds for use than a derringer.

So we’re back to what I said at the start:

Want some fun? Get an American Gun Craft 12ga double-barrel pistol.

Want a serious self/home defense gun? Get something else.

Jim Downey

The Cunningham Speed Strip

Anyone who has considered a revolver as a self-defense option has confronted the question of whether, and how, to carry spare ammunition for it. Loose cartridges are just a pain to deal with, and take forever to reload. Speedloaders are great, but more than a little bulky. Commercial ‘speed strips’ are less bulky, are commonly available at a reasonable price, and are a big improvement over fumbling with loose rounds, but can still be awkward for reloading quickly. That’s because while they hold six cartridges, they’re difficult to position such that you can load an empty cylinder quickly — the close-packed cartridges actually get in the way. One common trick for using a speed strip is to only put two pairs of cartridges in it, with a gap between the two sets and the last position empty — that way, you can always quickly load two sets of two adjacent chambers in the cylinder of your revolver. This technique is perhaps best known due to defensive revolver guru Grant Cunningham.

Well, after recently taking a class with Grant, and learning this technique, I set out to make a more functional speed strip which would completely and quickly reload any revolver. One that almost anyone can make on their own, with minimal tools and expense, and customized to their revolver, whatever cartridge it shoots and whatever the capacity of the cylinder. I jokingly call it the Cunningham Perfect & Adaptable Speed Strip for Any Revolver regardless of Caliber or Capacity. More seriously, I’ll refer to it as the Cunningham Speed Strip, (CSS for short.)

Here some pics of what it can look like:

And this is how you make it.

YOU’LL NEED:

Tools

- A pair of common pliers

- A hammer of almost any type

- A pair of scissors or utility knife

You’ll also need

- A Heat Source (just about anything from a hair dryer to a blowtorch will do — you’ll see)

- An empty cartridge case for your revolver

- A pen or pencil

- A sheet of paper (really, just a scrap)

- A scrap piece of heavy cardboard or wood

- Suitable piece of inexpensive common vinyl (more on this to come)

PROCEDURE:

Select your vinyl. A wide variety of commonly available types of vinyl will work. If you look at the examples above you’ll see a piece from a 1/2″ ID vinyl tube, a piece of vinyl floor runner, and a piece of vinyl sheet used to cover food for microwaving. In other words, a wide variety of vinyl materials are likely to work.

So experiment a little. What you want is to find a vinyl which is flexible (not rigid/brittle) and sufficiently thick to hold cartridges in position, but will easily pull away when you have the cartridges in the chambers of the cylinder. The vinyl tubing is the one I like the most, and is 1/16″ thick. It has a slight tackiness to the surface I like because it makes it easier to use. The vinyl sheet is about one-third that thick, and the vinyl floor runner is somewhere between the two (though a little too flexible for my tastes).

Now, realize that it’s likely that any of these materials will tear after repeated use. These aren’t meant to last forever … but each of my prototypes have held up to at least a dozen uses so far. The idea is that they’re cheap and easy to make and replace.

Cut the vinyl to rough size. You want a working piece that you can trim later. Here’s what the tubing looks like when cutting:

Make a paper template. It’s difficult to mark most kinds of vinyl. So the easy thing to do is to make a paper template of what you want. For a J-frame, you want two sets of paired cartridges and one solo, with gaps in between the sets (as shown). For other guns, you may want a different arrangement. But in each case you want to use your empty cartridge case to draw the position of the circles on the paper. Like so:

Also note that I have a couple of marks showing the approximate ends of the strip. You want a bit of a tab on either end, to make it easy to grab and use the strip. But the final amount (and whether square or rounded off) is entirely up to your preference.

Position the template and vinyl for punching. Here I recommend that you use either a piece of dense cardboard or a scrap piece of wood. You can tape down the template if you want. But position the template, then lay the strip of vinyl on top of it in alignment with the template.

Heat up the case and/or strip. Again, the source of the heat really won’t matter. It can be a heat gun. Or a warm brick. Or a hair dryer. Whatever you have handy. Now, this may not be necessary. With some vinyls, you don’t need to really heat them up. But I have found that it makes things easier if you do, as the vinyl becomes softer and more pliable. And you can see in the image above that I have a .38sp case positioned in front of a heat gun, to make it even easier.

Position the case and strike with a hammer. If you have heated up the case, or if you’re worried about smacking your fingers with the hammer, the easy thing to do is to pick up the case with a common pair of pliers and then hold it in position. Put the mouth of the case over the vinyl/template in the correct position, then hit the case with the hammer.

How hard to hit, or how many times, will depend. But ideally, you want to have the case punch through the vinyl in a clean and complete way, so you have a small disk of removed vinyl left. This is the advantage of using the case instead of trying to cut the vinyl with a knife or drill bit: you wind up with a good clean cut the *exact* size of the cartridge.

Repeat as many times as necessary. Until you have all the holes punched out.

Then trim the strip as desired. Once done, insert loaded cartridges and it’s ready to use.

That’s it!

I thought about patenting this idea, or seeing if I could sell it to some manufacturer. But it seemed like a good thing to just share as an ‘open source’ idea with the firearms/self-defense community so it could be used widely. If you found this instructional post useful in making your own customized speed strips, and would like to contribute a couple of bucks, just send a PayPal donation here: jimd@ballisticsbytheinch.com Proceeds will be shared with Grant Cunningham, who inspired this design.

Jim Downey

Handgun caliber and lethality.

This post is NOT about gun control, even though the article which it references specifically is. I don’t want to get into that discussion here, and will delete any comments which attempt to discuss it.

Rather, I want to look at the article in order to better understand ‘real world’ handgun effectiveness, in terms of the article’s conclusions. Specifically, as relates to the correlation between handgun power (what they call ‘caliber’) and lethality.

First, I want to note that the article assumes that there is a direct relationship between caliber and power, but the terminology used to distinguish between small, medium, and large caliber firearms is imprecise and potentially misleading. Here are the classifications from the beginning of the article:

These 367 cases were divided into 3 groups by caliber: small (.22, .25, and .32), medium (.38, .380, and 9 mm), or large (.357 magnum, .40, .44 magnum, .45, 10 mm, and 7.62 × 39 mm).

And then again later:

In all analyses, caliber was coded as either small (.22, .25, and .32), medium (.38, .380, and 9 mm), or large (.357 magnum, .40, .44 magnum, .45, 10 mm, and 7.62 × 39 mm).

OK, obviously, what they actually mean are cartridges, not calibers. That’s because while there is a real difference in average power between .38 Special, .380 ACP, 9mm, and .357 Magnum cartridges, all four are nominally the same caliber (.355 – .357). The case dimensions, and the amount/type of gunpowder in it, makes a very big difference in the amount of power (muzzle energy) generated.

So suppose that what they actually mean is that the amount of power generated by a given cartridge correlates to the lethality of the handgun in practical use. Because otherwise, you’d have to include the .357 Magnum data with the “medium” calibers. Does that make sense?

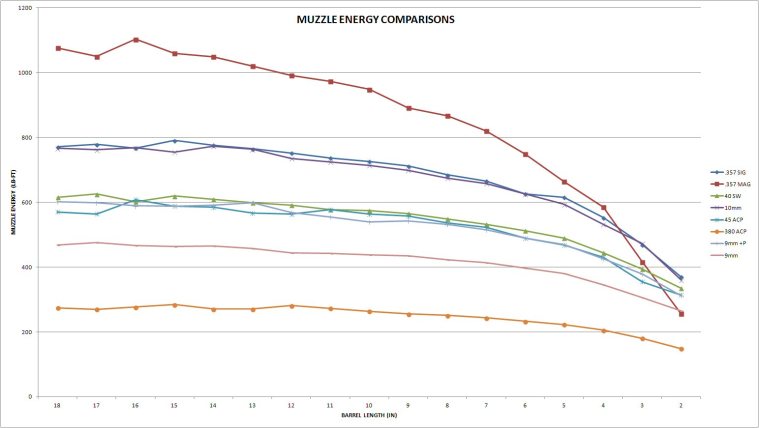

Well, intuitively, it does. I think most experienced firearms users would agree that in general, a more powerful gun is more effective for self defense (or for offense, which this study is about). Other things being equal (ability to shoot either cartridge well and accurately, concealability, etc), most of us would rather have a .38 Sp/9mm over a .22. But when you start looking at the range of what they call “medium” and “large” calibers, things aren’t nearly so clear. To borrow from a previous post, this graph shows that the muzzle energies between 9mm+P, .40 S&W, and .45 ACP are almost identical in our testing:

Note that 10mm (and .357 Sig) are another step up in power, and that .357 Mag out of a longer barrel outperforms all of them. This graph doesn’t show it, but .38 Sp is very similar to 9mm, .45 Super is as good as or better than .357 Mag, and .44 Magnum beats everything.

So, what to make of all this? This claim:

Relative to shootings involving small-caliber firearms (reference category), the odds of death if the gun was large caliber were 4.5 times higher (OR, 4.54; 95% CI, 2.37-8.70; P < .001) and, if medium caliber, 2.3 times higher (OR, 2.25; 95% CI, 1.37-3.70; P = .001).

certainly seems to carry a lot of import, but I’m just not sure how much to trust it. My statistical skills are not up to critiquing their analysis or offering my own assessment using their data in any rigorous way. Perhaps someone else can do so.

I suspect that what we actually see here is that there is a continuum over a range of different handgun powers and lethality which includes a number of different factors, but which the study tried to simplify using artificial distinctions for their own purposes.

Which basically takes us back to what gun owners have known and argued about for decades: there are just too many factors to say that a given cartridge/caliber is better than another in some ideal sense, and that each person has to find the right balance which makes sense for themselves in a given context. For some situations, you want a bigger bullet. For other situations, you want a smaller gun. And for most situations, you want what you prefer.

Jim Downey

Review: AMT Lightning — the Ruger Mk II Clone

I recently had a chance to shoot an AMT Lightning — it’s a clone of the Ruger Mark II .22lr pistol, but in stainless steel. Here it is:

That’s a 10″ factory barrel, which was one of the options available when these guns were being produced back in the 80’s/90’s.

I remember these guns, or more accurately the lawsuit about them, from when they were being produced. Ruger didn’t take kindly to AMT using their designs (AMT also had a version of the 10/22), and took them to court over it. Ruger won the suit, as I recall (though there isn’t much readily available online to document that) and a few years later AMT went belly-up. Whether that was a result of the lawsuit or poor sales is still a subject of some debate.

Anyway, these guns are still kicking around, and every so often you can see one in a local gun shop or on your favorite auction site. My buddy picked one up, and we shot it last weekend.

In checking online, it seems that the quality control on the AMT guns varied widely — from year to year, specific model guns could range from great and reliable to a major nightmare. Evidently the biggest problem was with the hardness of the stainless steel used.

Only time will tell, but the one we had seemed fine. The fit & finish were OK, with no obvious problems. It shot just fine, and didn’t feel much different than any Mark II I’ve ever shot, though the trigger seemed a little rougher. Without doing a head-to-head comparison, I can’t really say much more than that. Accuracy was as good as I could expect, limited more by my ability shooting it standing than by any issues with the gun. The long barrel certainly made it soft to shoot in terms of recoil.

So I wouldn’t call it a collector’s item, or comparable in quality to a real Ruger. But if you come across one at an attractive price, and it looks to be in decent shape, don’t be afraid to take a risk.

Jim Downey

Review: Browning 1911-380

Over the weekend I had a chance to try one of the relatively new Browning 1911-380 models. It was one of the basic models, with a 4.25″ barrel:

I like a nice 1911, and have owned several over the years. I even like a ‘reduced’ 1911, such as the Springfield EMP (a gun I still own and love), and I have previously shot the Browning 1911-22 , which I liked quite a lot more than I expected. So I was excited to give the new .380 ACP version a try.

What did I think? Well, I liked it. About as much as I liked the .22 version, though of course the guns are intended for two very different things. I see the 1911-22 as being a great gun for learning the mechanics of the platform, and building up your skill set with less expensive ammo. It’s also a lot of fun just for plinking, as are many .22 pistols.

But the 1911-380 is very much intended as a self-defense gun, and that is how it is marketed and has generally been reviewed. From the Browning website:

Conceals better. It is easily concealed with its smaller size and single-stack magazine that offer a compact, flat profile that fits easily inside the waistband and keeps the grip narrow for shooters with smaller hands.

They also tout modern .380 ACP ammo for self-defense. Which I will agree with, but not enthusiastically — even out of a longer barrel, I consider it sufficient, but only that.

Still, the extra sight radius and weight of the 1911-380 does make it a better self-defense gun than sub-compact and micro .380s, and plenty of people are happy to rely on those. Though those advantages come with a cost: this is NOT a pocket pistol. Still, anyone who may be recoil shy but still wants an adequate self-defense round should check out the 1911-380. It is small enough to conceal well, and follow-up shots are very quick and easy to control.

One thing I really didn’t like were the sights. The matte black sights on the matte black slide were almost impossible for my old eyes to find and use quickly. Seriously, look at this image from the Browning site:

And that makes it look better than it did out at the range. Even just a white dot/white outline would have been a great improvement, and I’m honestly surprised that Browning seems to have made no effort at all to make them more effective. If I got one of these guns, the very first thing I would do would be to upgrade the sights, even if that meant just adding a dab of paint.

So there ya go: if you’re in the market for a low-recoil, quality made, 1911 platform self-defense gun, check out the Browning 1911-380. But if you get one, do something with the sights on the damned thing.

More complete reviews can be found all over the web. This one is fairly typical in having positive things to say.

Jim Downey

Reprise: Is the Ruger LCR a perfect concealed carry revolver?

Prompted by my friends over at the Liberal Gun Club, this is another in an occasional series of revisiting some of my old articles which had been published elsewhere over the years, perhaps lightly edited or updated with my current thoughts on the topic discussed. This is an article I wrote for Guns.com, and it originally ran 5/3/2012. Some additional observations at the end.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Sturm, Ruger & Company line of LCR composite-frame revolvers have been available for a few years now (2009) and since expanded from the basic .38 Special that weighs 13.5 ounces, to a 17-ounce version that can handle full .357 magnum loads, and a slightly heavier one that shoots .22 Long Rifle.

Ruger makes excellent firearms and I have grown up with them, but I was more than a little skeptical at the prospect of a revolver with a composite frame when I first heard about it. And the initial images released of the gun didn’t belay my skepticism.

But then the first Ruger LCR revolvers were actually introduced and I found out more about them. The frame is actually only partly composite while the part that holds the barrel, cylinder, and receiver is all aluminum. The internal components like the springs, firing pin, trigger assembly, et cetera are all housed in the grip frame and are well supported and plenty robust. My skepticism turned to curiosity.

When I had a chance to actually handle and then shoot the LCR, my curiosity turned to enthusiasm. Since then, having shot several different guns of both the .38 Special and .357 LCR models, I have become even more impressed. Though I still think the LCR is somewhat lacking in the aesthetics department. But in the end it does what it is designed to do.

Like the S&W J-frame revolvers, the models it was meant to compete with, the LCR is an excellent self-defense tool. It’s virtually the same size as the J-frames and the weight is comparable (depending on which specific models you’re talking about). So it hides as well in a pocket or a purse because it has that same general ‘organic’ shape.

The difference is, the LCR is, if anything, even easier to shoot than your typical J-frame Double Action Only revolver (DAO, where the hammer is cocked and then fired in one pull of the trigger). I’m a big fan of the Smith & Wesson revolvers, and I like their triggers. But the LCR has a buttery smooth, easy-to-control trigger right out of the box, which is as good or better than any S&W. Good trigger control is critical with a small DAO gun and makes a world of difference for accuracy at longer distances. I would not have expected it, but the LCR is superior in this regard.

Like any snub-nosed revolver, the very short sight radius means that these guns can be difficult to shoot accurately at long distance (say out to 25 yards). But that’s not what they are designed for. They’re designed to be used at self-defense distances (say out to seven yards). And like the J-frame DAO models, even a new shooter can become proficient quickly.

I consider the .38 Special model sufficient for self defense. It will handle modern +P ammo, something quite adequate to stop a threat in the hands of a competent shooter. And the lighter weight is a bit of an advantage. But there’s a good argument to be made for having the capability to shoot either .38 Special or .357 magnum cartridges.

My only criticism of the LCR line is that they haven’t yet been around long enough to eliminate potential aging problems. All of the testing that has been done suggests that there won’t be a problem and I trust that, but only time will truly tell if they hold their value over the long haul.

So, there ya go. To paraphrase what I said about the S&W Centennial models: “Want the nearly perfect pocket gun? You’d be hard pressed to do better than a Ruger LCR.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

It’s been six years since I wrote this, which means the early versions of the LCR have now been around for almost a decade. And as far as I know, there hasn’t yet been a widespread problem with them holding up to normal, or even heavy, use. So much for that concern.

And Ruger has (wisely, I think) expanded the cartridge options for the LCR even further. You can still get the classic 5-shot .38 Special and .357 Magnum versions, as well as the 6-shot .22 Long Rifle one. But now you can also get 6-shot .22 Magnum or .327 Magnum versions, as well as a 5-shot offering in 9mm. Each cartridge offers pros and cons, of course, as well as plenty of opportunity for debate using data from BBTI. Just remember that the additional of the cylinder on a revolver effectively means you’re shooting a 3.5″ barrel gun in the snubbie model, according to our charts. Personally, I like this ammo out of a snub-nosed revolver, and have consistently chono’d it at 1050 f.p.s. (or 386 foot-pounds of energy) out of my gun.

For me, though, the most exciting addition has been the LCRx line, which offers an exposed hammer and SA/DA operation:

I like both the flexibility of operation and the aesthetics better than the original hammerless design. But that’s personal preference, nothing more.

The LCR line has also now been around long enough that there are a wide selection of accessories available, from grips to sights to holsters to whatever. Just check the Ruger Shop or your favorite firearm supply source.

So, a perfect pocket gun? Yeah, I think so. Also good for a holster, tool kit, or range gun.

Jim Downey

Reprise: NAA .22 Mini-Revolver Review

Prompted by my friends over at the Liberal Gun Club, this is another in an occasional series of revisiting some of my old articles which had been published elsewhere over the years, perhaps lightly edited or updated with my current thoughts on the topic discussed. This is an article I wrote for Guns.com, and it originally ran 1/23/2012. Some additional observations at the end.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

North American Arms makes a selection of small semi-auto pistols, but they are perhaps best known for their series of Mini-Revolvers in a variety of different .22 caliber cartridges. They currently offer models in .22 Short, .22 Long Rifle, .22 Magnum, and a .22 Cap and Ball. This review is specifically about the .22 LR model with a 1 1/8-inch barrel, but the information is generally applicable to the other models of Mini-Revolvers that NAA offer as well.

The NAA-22LR is very small, and would make an almost ideal ‘deep cover’ or ‘last ditch’ self-defense firearm. It isn’t quite as small as the .22 Short version, which has a shorter cylinder, and it doesn’t have quite the same power level as the .22 Magnum version either. It has a simple fixed-blade front sight that has been rounded to minimize snagging and it holds five rounds.

All the NAA revolvers I have seen or shot are very well made. They’re solid stainless steel construction, and use high-quality components for all other parts. The fit and finish is quite good, and there is nothing at all shoddy about them. The company also has a solid reputation for standing behind these guns if there is a problem.

The NAA-22LR is surprisingly easy to shoot. I have very large hands, and very small guns are usually a problem for me to shoot well. But most of the really small handguns I have shot are semi-automatics, which impose certain requirements on proper grip. The NAA Mini-Revolvers are completely different. First, they are Single Action only, meaning that you have to manually cock the hammer back before the gun will fire. Second, there is no trigger guard – something which may make novice shooters nervous. However, since the trigger does not extend until the hammer is drawn back, there really isn’t a safety issue with no trigger guard.

Further, the NAA Mini-Revolvers use an old trick of having the hammer rest on a ‘half-notch’ in what they call their “safety cylinder”. This position is between chambers in the cylinder, and ensures that the gun cannot fire when it is dropped. Again, you have to manually cock back the hammer in order to get the cylinder to rotate and then it’ll align a live round with the hammer.

One option available on most of the Mini-Revolvers is their “holster grip”, which is a snap-open grip extension that also serves as a belt holster by folding under the bottom of the gun. It is an ingenious design and makes it much easier to hold and fire the gun.

About the only problem with the gun is a function of its very small design: reloading. You have to completely remove the cylinder, manually remove spent cases, load new rounds into each chamber, and then remount the cylinder. This is not fast nor easy, and effectively turns the gun into a “five shot only” self-defense gun. But realistically, if you’ve gotten to the point where you are relying on a NAA Mini-revolver for self defense, I have a hard time imaging there would be much of an opportunity to reload the thing regardless.

Another point to consider with the NAA-22LR: ballistics. We did test this model as part of our BBTI .22 test sequence. Suffice it to say that the 1 1/8-inch barrel had the poorest performance of any gun we tested in terms of bullet velocity/power, which is to be expected, and is a trade-off for the very small size of these guns. If you want to check the data, use the 2″ barrel row for approximate results.

Bottom line, the NAA Mini-Revolvers serve a very specific purpose, and are well-suited to that purpose.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

There’s a fair amount I’d like to add to this post, since NAA has expanded their selection of mini-revolvers considerably, and there are some intriguing new models.

But first I’d like to point out that they’ve added some really solid ballistics information to their site for each of the models. Seriously, they give excellent information about what performance you can expect with a variety of ammo, and as far as I can see the results are very realistic in comparison to our own data. Just one ammo example for the model above:

| Tests with NAA-22LLR, S/N L15902 | Tests with NAA-22LLR, S/N L15901 | ||||||

| CCI Green Tag | |||||||

| 40 Gr. Solid | 1st Group | 2nd Group | Avg. | 1st Group | 2nd Group | Avg. | 2 Gun Avg. |

| High | 598 | 609 | 604 | 666 | 609 | 638 | 621 |

| Low | 581 | 529 | 555 | 495 | 568 | 532 | 543 |

| Mean | 588 | 575 | 582 | 594 | 585 | 590 | 586 |

| SD | 7 | 29 | 18 | 63 | 15 | 39 | 29 |

That is extremely useful information, well organized and presented. Kudos to North American Arms for doing this! I’m seriously impressed.

As I noted, they’ve also added a number of new model variations to their offerings. Now you can get models with slightly oversized grips, with 2.5″, 4″, and 6″ barrels (in addition to the 1 1/8-inch barrel and 1 5/8-inch barrel models), with Old West styling, and a selection of different sight types & profiles. They even have a laser grip option available.

But perhaps even more excitedly, they now have both Swing-out and Break-top models which eliminate the problems with reloading:

Sidewinder with 2.5″ barrel

RANGER-II-Break-Top.

Cost for those models are unsurprisingly higher than the older & simpler models, but still fairly reasonable.

I think that all models have a conversion-cylinder option available, so you can shoot either .22lr or .22mag ammo. As I have noted previously, at the very low end there’s not much additional power of .22mag over .22lr, but having the ability to switch ammo can still be worthwhile. And certainly, when you start getting out to 4″ (+ the cylinder), there is a greater difference in power between the two cartridges, and I think that if you were to get one of the guns with the longer barrel it would make a whole lot of sense to have the ability to shoot both types of ammo.

I’ll close with this thought: think how much fun it would be to have one of these mini-revolvers in something like .25 or .32 acp configured to carry say three rounds. Or you could even go nuts with a .32 H&R or .327 mag … 😉

Jim Downey

Reprise: When is a Magnum not really a Magnum?

Prompted by my friends over at the Liberal Gun Club, this is another in an occasional series of revisiting some of my old articles which had been published elsewhere over the years, perhaps lightly edited or updated with my current thoughts on the topic discussed. This is an article I wrote for Guns.com, and it originally ran 6/5/2013. Some additional observations at the end.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Those are all claims taken right off of the box of three different boxes of .22 Magnum (technically, the .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire cartridge) ammo. And when you see numbers like those, it’s really easy to get excited about how much more powerful the .22 Magnum is over your standard .22 LR.

But what do those numbers really mean? And can you really expect to get that kind of performance? Do you get a different kind of performance out of your rifle than you get out of your little revolver?

That’s one of the reasons that our Ballistics By The Inch project exists: to find out just exactly what the reality of handgun cartridge performance is, and to see how it varies over different lengths of barrel.

And the first weekend of May, we did a full sequence of tests of 13 different types of .22 Magnum ammo to find out.

About our tests

About four years ago we started testing handgun cartridges out of different lengths of barrel, using a Thompson/Center Encore platform, which has been altered to allow a number of different barrels to be quickly mounted. The procedure is to set up two chronographs at a set distance from a shooting rest, and fire three shots of each type of ammo, recording the results. Once we’ve tested all the ammo in a given caliber/cartridge, we chop an inch off the test barrel, dress it, and repeat the process, usually going from an 18-inch starting length down to 2 inches. The numbers are then later averaged and displayed in both table and chart form, and posted to our website for all to use.

For those who are interested in the actual raw data sets, those are available for free download. To date we’ve tested over 25,000 rounds of ammunition across 23 different cartridges/calibers.

To do the .22 Magnum tests things were slightly different. We started with a Thompson .22 “Hot Shot” barrel and had it re-chambered to .22 Magnum. Since this barrel started out 19-inches long, we included that measurement in our tests.

So, how did the .22 Magnum cartridge do?

See those claims from manufacturers at the top of this article? Two of the three were supported by our test results. The third was not.

Data sheet from the test.

I don’t want to pick on those specific brands/types of ammo, though. I just grabbed three of the boxes we tested at random. Altogether we tested 13 different brands/types of .22 Magnum ammo, and let’s just say that the performance you actually see out of your gun will probably vary from what you see claimed from a manufacturer.

Now, that’s not because the ammo manufacturers are lying about the performance of their ammo. Rather, the way they test their ammo probably means that it isn’t like how you will use their ammo. This is most likely due to the fact that the barrel length and testing conditions are pretty different than your typical “real world” gun.

So, what can you expect from a .22 Magnum cartridge?

Well, that pretty much depends on how long a barrel you have on your gun.

Most handgun cartridges show a really sharp drop-off in velocity/power out of really short barrels. Typically, going from a 2- to 3-inch barrel makes a bigger difference than going from a 3- to 4-inch barrel.

Also typically, most handgun cartridges tend to level out somewhere around 6 to 8 inches. Oh, they usually gain a bit more for each inch of barrel after that, but the increase each time is increasingly small.

The real exception to this, as I have noted previously, are the “magnum” cartridges: .327 Magnum, .357 Magnum, .41 Magnum and .44 Magnum. The velocity/power curves for all these tend to climb longer, and show more gain, all the way out to 16 to 18 inches or more. There are exceptions to all these rules, but the trends are pretty clear.

So, does the .22 Mag deserve to be listed with the other magnum cartridges?

Well — maybe. Compared to the .22 LR, the .22 Magnum gains more velocity/power over a longer curve. But it also starts to flatten out sooner than the other magnums — usually at about 10 to 12 inches. Like most handgun cartridges, there are gains beyond that, but they tend to be smaller and smaller.

Bottom line

For me, the take-away lesson from these tests is that the .22 Magnum is a cartridge that is best served out of rifle barrel, even a short-barreled rifle. At the high end we were seeing velocities that were about 50 percent greater than what you’d get out of a similar weight bullet from a .22 LR. In terms of muzzle energy, there’s an even bigger difference: 100 percent or more power in the .22 Magnum over the .22 LR.

But when you compare the two on the low end, out of very short barrels, there’s very little if any difference: about 10 percent more velocity, perhaps 15 percent more power. What you do notice on the low end is a lot more muzzle flash from the .22 Magnum over .22 LR.

As you can see, there’s not a whole lot of rifling past the end of the cartridge when you get *that* short.

While you do see a real drop-off in velocity for the other magnums from very short barrels, they tend to start at a much higher level. Compare the .357 Magnum to the .38 Special, for example, where the velocity difference is 30 to 40 percent out of a 2-inch barrel for similar weight bullets, with a muzzle energy difference approaching 100 percent. Sure, you get a lot of noise and flash out of a .357 snubbie, but you also gain a lot of power over a .38.

But then there’s the curious case of the Rossi Circuit Judge with an 18.5-inch barrel, chambered in .22 Magnum. You see, it only performed as well as my SAA revolver with the 4.625-inch barrel. This was so completely unexpected that we thought we had to have made a mistake, or the chronos were malfunctioning, or something. So we went back and tested other guns for comparison. Nope, everything was just fine, and the other guns tested as expected.

So we made a closer examination of the Rossi and it just goes to show where there’s a rule, there’s an exception. Yup, there’s a good reason why it was giving us the readings it was. And I’ll reveal why when I do a formal review of that gun.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

OK, first thing I want to say: the reason the Circuit Judge performed so poorly was that it had a forcing cone the size of a .357 magnum on it, either allowing far too much gas to escape as the bullet made the transition from the cylinder to the barrel or because the chamber was so badly out of alignment with the barrel that it was necessary for the bullet to be guided into the barrel by first striking the side of the cone. Either way, it was a problem.

Next thing: since I wrote this 4+ years ago, I have seen countless examples of people insisting that even a little NAA .22mag pistol is MUCH more powerful than the .22lr version.

No, the .22mag is not more powerful at those very short barrel lengths. It isn’t until you get to 5 – 6″ that the .22mag starts to really outperform the .22lr. Take a look at the Muzzle Energy charts yourself:

This is not to dis the .22mag. It’s a fine cartridge — in the right application. For me, that means out of a rifle. And there are good reasons to have a handgun chambered in .22mag, such as ammo compatibility with a rifle or just flexibility in ammo availability in the case of a convertible revolver like the one I have. Just understand what the real advantages and disadvantages actually are before you make a decision.

Jim Downey

Reprise: Review of the finest revolver ever made — the Colt Python

Prompted by my friends over at the Liberal Gun Club, this is another in an occasional series of revisiting some of my old articles which had been published elsewhere over the years, perhaps lightly edited or updated with my current thoughts on the topic discussed. This is an article I wrote for Guns.com, and it originally ran 1/12/2012. Some additional observations at the end.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Who in their right mind would pay $1,200 . . . $1,500 . . . $2,000 . . . or more for a used production revolver? Lots of people – if it is a Colt Python.

There’s a reason for this. The Colt Python may have been a production revolver, but it was arguably the finest revolver ever made, and had more than a little hand-fitting and tender loving care from craftsmen at the height of their skill in the Colt Custom Shop.

OK, I will admit it – I’m a Python fanboy. I own one with a six-inch barrel, which was made in the early 1980s. And I fell in love with these guns the first time I shot one, back in the early 1970s. That’s my bias. Here’s my gun:

But the Python has generally been considered exceptional by shooters, collectors, and writers for at least a generation. Introduced in 1955, it was intended from the start to be a premium revolver – the top of the line for Colt. Initially designed to be a .38 Special target revolver, Colt decided instead to chamber it for the .357 Magnum cartridge, and history was made.

What is exceptional about the Python? A number of different factors.

First is the look of the gun. Offered originally in what Colt called Royal Blue and nickel plating (later replaced by a polished stainless steel), the finish was incredible. The bluing was very deep and rich, and still holds a luster on guns 40 to 50 years old. The nickel plating was brilliant and durable, much more so than most guns of that era. The vent rib on top of the barrel, as well as the full-lug under, gave the Python a distinctive look (as well as contributing to the stability of shooting the gun). It had excellent target sights, pinned in front (but adjustable) and fully adjustable in the rear.

The accuracy of the Python was due to a number of factors. The barrel was bored with a very slight taper towards the muzzle, which helped add to accuracy. The way the cylinder locks up on a (properly functioning) Python meant that there was no ‘play’ in the relationship between the chamber and the barrel. The additional weight of the Python (it was built on a .41 Magnum frame for strength) helped tame recoil. And the trigger was phenomenally smooth in either double or single action. Seriously, the trigger is like butter, with no staging or roughness whatsoever – it is so good that this is frequently the thing that people remember most about shooting a Python.

The Python had minimal changes through the entire production run (it was discontinued effectively in 1999, though some custom guns were sold into this century). It was primarily offered in four barrel lengths: 2.5-, 4-, 6-, and 8-inch, though there were some special productions runs with a three-inch barrel. Likewise, it was primarily chambered in .357 Magnum, though there were some special runs made in .38 Special and .22 Long Rifle.

The original grips were checkered walnut. Later models had Pachmayr rubber grips. Custom grips are widely available, and very common on used Pythons (such as the cocobolo grips seen on mine).

The Python was not universally praised. The flip side of the cylinder lock-up mechanism was that it would wear and get slightly out-of-time (where the chamber alignment was no longer perfect), necessitating gunsmith work. Mine needs this treatment, and I need to ship it off to Colt to have the work done. And the high level of hand-finishing meant that the Python was always expensive, and the reason why Colt eventually discontinued the line.

If you have never had a chance to handle or shoot a Python, and the opportunity ever presents itself, jump on it. Seriously. There are very few guns that I think measure up to the Python, and here I include even most of the mostly- or fully-custom guns I have had the pleasure of shooting. It really is a gun from a different era, a manifestation of what is possible when craftsmanship and quality are given highest priority. After you’ve had a chance to try one of these guns, I think you’ll begin to understand why they have held their value to a seemingly irrational degree.

On average, for online gun sellers, the Colt Python sells for more than $2,000, but there are occasions where you’ll find it for less than a grand.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The value of the Pythons has continued to rise in the almost six years since I wrote that, and I’m just glad I got it before the market went nuts. I haven’t seen one sell for less than a thousand bucks in years.

I did send my Python off to Colt to have it re-timed before the last of the smiths who had originally worked on the guns retired, and it came back in wonderful condition. I don’t know what all they did to it, but it cost me a ridiculously modest amount of money — like under $100. It was clear that there was still a lot of pride in that product.

Whenever I get together with a group of people to do some shooting, I usually take the Python along and encourage people to give it a try. More than a few folks have told me that it was one of their “Firearms bucket list” items, and I have been happy to give them a chance to check it off. Because, really, everyone who appreciates firearms should have a chance to shoot one of these guns at some point in their lives — it’d be a shame to just leave such a gun in the safe.

Jim Downey

Reprise: Give in to the Power of the Dark Side — Converting Non-shooters

Prompted by my friends over at the Liberal Gun Club, this is another in an occasional series of revisiting some of my old articles which had been published elsewhere over the years, perhaps lightly edited or updated with my current thoughts on the topic discussed. This is an article I wrote for Guns.com, and it originally ran 8/5/2011. Some additional observations at the end.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I swear, sometimes I feel like a Sith Lord.

Friends and acquaintances will find out that I’m “into” guns. We’ll be chatting and there will be this odd moment where I can see it in their eyes: attraction, mixed with not a little fear.

If they know me at all, either through interaction or by reputation, they probably have a certain expectation. I’m a professional book & document conservator. I used to own a big art gallery. For years I wrote a column about the arts for the local newspaper. I even gained some small measure of fame as a conceptual artist. I was the primary care-provider for my elderly mother-in-law, and have been praised for my gentleness and compassion. I’ve published two books, and am working to complete a third. Based on that, they have probably put me into a nice little box in their mental map of the world.

That I am a gun owner, someone with a CCW, and even one of the principals behind the world’s premier handgun ballistics resource usually comes as a bit of a surprise.

Hahahahahahahaha!

Yes, I like this reaction. I like what it does to people: forces them to reconsider some of their stereotypes.

And I also like that it gives me the opportunity to tempt them. To corrupt them. By taking them shooting.

What can I say? I’m evil. You know, like a Dark Lord of the Sith.

Bwahahahaha!

I don’t know how many people I have done this to. Not enough. I want to turn more of them. To have them hold a gun in their hands, to learn how they can control it, to use it safely.

Because I have found that this is key – turning their fear of something they do not understand into a tool that they can use. I tap into the strong emotion of fear, subvert it, direct it. It becomes a motivator. It helps them understand that a gun needs to be respected and handled safely.

We go through the formula of the Four Rules. They handle the revolver, the pistol, and the rifle before the ammunition ever comes out of storage. We study cartridge, and bullet, and caliber. And then I reveal the mysteries of sighting, breathing, and trigger control.

We go to the range. There is the ritual of eye and hearing protection. A review of safety commands. An invocation of the formula of the Four Rules.

I take out a .22 rifle. Load it with one round only. Tension builds. I am down range at a simple target and fire the gun.

Now they’re almost hooked. There’s anticipation, almost a hunger as they watch me.

I check the gun to make sure it is unloaded. Hand it over, have them check it. Give them one round, have them load it. Carefully, they seat the rifle, take aim. When they are ready, I have them click off the safety, put their finger on the trigger and squeeze.

You can see it in their eyes. A part of them has come alive. A part they feared. Because they did not understand it.

Usually, they get a big smile on their face. Or maybe that comes later, when we shoot one of the handguns. Sometimes it takes until we get to one of the magnums, something with a real kick to it. A big badda-BOOM! But when that happens, every one of them is hooked.

Oh, not necessarily hooked in the sense of going out and getting their own guns, and taking up shooting sports as a lifetime activity. No, hooked in the sense of understanding at an almost cellular level what the appeal is: the ability to control a kind of power they never had before.

I have opened up a whole new world for them. Shown them possibilities they didn’t know existed. Gave them a taste of the potential they had locked away.

Some of them do get hooked in the sense of wanting to learn how to use that potential. They start asking me about the nuts and bolts of getting their own gun, what it takes to pass the state CCW requirements, the advantages of this caliber or that design. They become a convert.

But even if they don’t, they no longer have an irrational fear of guns because they now know something about them – something practical and hands-on—you can almost watch their stereotyping melt and wash away. They understand that guns are not inherently “evil” – they’re just a tool, which can be used by anyone willing to put in the time to learn how to do so.

And as we pack up from our trip to the range, I’ll usually joke that I have “turned them to the Dark Side.”

Like the good Sith Lord that I am.

Wahahahaha!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Yeah, OK, now you know why I’m not the “Jim Downey” who was an SNL writer.

But I was trying to have a little fun with the idea of ‘turning’ someone on the subject of firearms, because it is a very real experience I’ve had countless times.

Jim Downey

Reprise: Love me, love my gun — Gun Ownership and Your Non-Shooting Significant Other

Prompted by my friends over at the Liberal Gun Club, this is another in an occasional series of revisiting some of my old articles which had been published elsewhere over the years, perhaps lightly edited or updated with my current thoughts on the topic discussed. This is an article I wrote for Guns.com, and it originally ran 10/10/2011. Some additional observations at the end.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Many years ago, as we were packing up our gear after a successful hunt, one of my buddies confided to me that this might be the last pheasant season that we shared.

“Why? You OK? What is it, heart problems or cancer or something?”

“Worse. Joan doesn’t like guns, doesn’t want any in the house after we get married.”

* * *

I was lucky. When my wife and I got together, she already owned a gun. Granted, it was an old Winchester Model 63 she had inherited from her dad, but still it meant that guns weren’t an issue for us at all, and haven’t been for the almost 24 years we’ve been married.

But like my buddy above, I’ve had any number of friends who have had to navigate this issue with a spouse or ‘significant other’ (SO henceforth) – and it hasn’t always broken down along predictable gender lines, either.

It’s a tough problem. Sure, you can try to educate, or get your SO interested in shooting or hunting or self-defense, but that doesn’t always work. Chances are they may well see the problem in the same light: as requiring education to “enlighten” you as to the dangers of having a gun in the home. It’s always worth keeping in mind that someone who is ‘anti’ may be operating from their position with as much conviction and good intent as you have in being ‘pro’.

So, what do you do? Just move along to see if you can find another fish in the sea? That seems to be the first instinct, judging from how I have seen this topic discussed on countless gun sites over the years.

But love doesn’t always work out that way. It’s messy. It’s sometimes unpredictable. And every relationship I’ve ever been in or seen has required some compromises and accommodation of another’s likes and dislikes. My wife hates hot spices, while I grow super-hot varietals of Habaneros which I love in almost every dish. And I cannot grok her love of musicals of any stripe. It’d be silly, or at least short-sighted, for us to give up on our marriage over either of these trivial things.

Where do you draw the line, though?

Well, that’s the question, isn’t it? How do you decide what is more important: your love for another, or your love of guns. Your happiness in sharing a life, or your fundamental belief in the 2nd Amendment.

I know that none of my guns are more important to me than my wife. I’d give up every single one of them, if it was a matter of her life or them, just as I would give my life to protect her. Those who have given an oath to defend the Constitution may well feel the same way about the Right to Keep and Bear Arms.

But is that the right way to think about it? Do you really need to put this question into such absolute terms?

If anything, a relationship is about nuance. Trying to define everything in terms of black and white is unlikely to be productive to a long and happy marriage. The trick is to find a way to make the relationship work without compromising your principles. To go back to my trivial examples, I have a variety of hot sauces and ground Habanero powder that I add to dishes after I’ve taken my portion. My wife enjoys musicals on her own or with a friend.

And my buddy kept his guns at his parent’s place. Well, for a while. It wasn’t long before his wife got comfortable enough with the notion of his hunting that he started just bringing them home with him at the end of a day out in the field. I think that it helped that she decided she liked the taste of pheasant.

So, it might work to just get a safe (which you should have, anyway). Or to give your SO the key to your safe so they don’t have to fear anyone getting to the guns without their approval. Or to keep your guns at someone else’s abode. Or maybe to only have long guns, not those evil evil handguns. Or some other compromise.

Things change over time. So do people. The danger in any relationship comes from trying to change your SO, rather than just growing together and seeking to enrich one another’s lives. Trying to indoctrinate is unlikely to work, whereas sharing information may very well. Isn’t sharing the joys and sorrows of life what it is all about, anyway?

Like I said, I was lucky. Not only did my wife not have a problem with guns in our home, she’s come to share some of my enthusiasm for the shooting sports. Now we enjoy getting out to the range together whenever we can. The only thing I have to watch out for is her deciding that she likes some of my guns better than I do. But I don’t mind sharing. Don’t mind it at all.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

My wife and I are now closing in on our 30th anniversary, and if anything she’s more supportive of my interest in guns now than when I wrote this.

And in the intervening six years, we’ve also seen something of a shift in the culture. Now more people are interested in guns, and it is easier than ever for the law-abiding to carry a weapon for self-defense. Sure, there are still plenty of problems with violence and crime, some of which involves firearms. But as a general thing the perception is that firearms don’t automatically mean more violence, and owning them doesn’t carry the same stigma that it did. So I think that perhaps it is now easier for people who have a non-shooting SO to make an argument for their having firearms.

Your thoughts?

Jim Downey

Reprise: Is Muzzle Energy Really a Measure of Handgun Effectiveness?

Prompted by my friends over at the Liberal Gun Club, this is another in an occasional series of revisiting some of my old articles which had been published elsewhere over the years, perhaps lightly edited or updated with my current thoughts on the topic discussed. This is an article I wrote for Guns.com, and it originally ran 2/13/2012. Some additional observations at the end.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Would you rather be shot with a modern, Jacketed Hollow Point bullet from a .32 ACP or have someone throw a baseball at you? Seems like a silly question, doesn’t it? But did you know that the ‘muzzle energy’ of the two is about the same? Seriously, it is and that’s just one reason why trying to use muzzle energy as a measurement of handgun effectiveness is problematic.

Calculating Muzzle Energy

First off, what is ‘muzzle energy’ (ME)? Wikipedia has a pretty good description and discussion of it. Here’s the simple definition:

Muzzle energy is the kinetic energy of a bullet as it is expelled from the muzzle of a firearm. It is often used as a rough indication of the destructive potential of a given firearm or load. The heavier the bullet and the faster it moves, the higher its muzzle energy and the more damage it will do.

For those who are trying to remember your high school physics, kinetic energy is the energy (or power) of something moving. You can calculate kinetic energy using the classic formula:

E = 1/2mv^2

Which is just mathematic notation for “Energy equals one-half the mass of an object times the square of its velocity.”

Doing the actual calculations can be a bit of a pain, since you have to convert everything into consistent units, but the formula is there on the Wikipedia page (and can be found elsewhere) if you want to give it a go. Fortunately, there are a number of websites out there which will calculate muzzle energy for you – you just plug in the relevant numbers and out comes the result. We also have muzzle energy graphs for all the calibers/ammunition tested at BBTI.

Batter up?

If you go through and check all the muzzle energy numbers for handguns with a 6″ or less barrel which we’ve tested (BBTI that is), in .22, .25. or .32, you’ll see that all except one (and you’ll have to go to the site to see which one it is) comes in under 111 foot-pounds.

Why did I choose that number? Because that would be the kinetic energy of a baseball thrown at 100 mph. Check my numbers: a standard baseball weighs 5.25 ounces, which is about 2,315 grains. 100 mph is about 147 fps. That means the kinetic energy of a baseball thrown at 100 mph is 111 ft-lbs.

Now, we’re not all pro baseball pitchers. And I really wouldn’t want to just stand there and let someone throw a baseball at me. But I would much rather risk a broken bone or a concussion over the damage that even a small caliber handgun would do.

The Trouble with Muzzle Energy

And therein lies the problem with using muzzle energy as the defining standard to measure effectiveness: it doesn’t really tell you anything about penetration. A baseball is large enough that even in the hands of Justin Verlander it’s not going to penetrate my chest and poke a hole in my heart or some other vital organ. If I catch one to the head, it may well break facial bones or even crack my skull, but I’d have a pretty good chance of surviving it.

Now, I think muzzle energy is a useful measure of how much power a given handgun has. That’s why we have it available for all the testing we’ve done on BBTI. But it is just one tool, and has to be taken into consideration with other relevant measures in order to decide the effectiveness of a given gun or caliber/cartridge. Like measures such as depth of penetration. And temporary and permanent wound channels. And accuracy in the hands of the shooter. And ease of follow-up shots. And ease of carry.

I’ve seen any number of schemes people have come up with to try and quantify all the different factors so that you can objectively determine the “best” handgun for self defense. Some are interesting, but I think they all miss the point that it is an inherently subjective matter, where each individual has to weigh their own different needs and abilities.

Sure, muzzle energy is a factor to consider. But I think the old adage of “location (where a bullet hits) is king, and penetration is queen” sums it up nicely.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In the five years since I wrote that, my thinking has evolved somewhat. Well, perhaps it is better to say that it has ‘expanded’. I still agree with everything above, but I’m now even more inclined to go with a relatively heavy bullet for penetration over impressive ME numbers. I think that comes from shooting a number of different brands of ammo where the manufacturer has chosen to go with a very fast, but very light bullet to get an amazing ME, with the argument that this is more likely to cause some kind of terminal shock, citing tests showing significant ‘temporary wound channels’ and such in ballistic gel.

But you really can’t cheat physics. If you dump a lot of kinetic energy very quickly into creating a temporary wound channel, then you have less energy for other things. Like penetration. Or bullet expansion. And those are factors which are considered important in how well a handgun bullet performs in stopping an attacker. That’s why the seminal FBI research paper on the topic says this:

Now, you can still argue over the relative merits of the size of the bullet, and whether a 9mm or a .45 is more effective. You can argue about trade-offs between recoil & round count. About this or that bullet design. Those are all completely valid factors to consider from everything I have seen and learned about ballistics, and there’s plenty of room for debate.

But me, I want to make sure that at the very minimum, the defensive ammo I carry will 1) penetrate and 2) expand reliably when shot out of my gun. And if you can’t demonstrate that in ballistic gel tests, I don’t care how impressive the velocity of the ammo is or how big the temporary wound cavity is.

So I’ll stick with my ‘standard for caliber’ weight bullets, thanks. Now, if I can drive those faster and still maintain control of my defensive gun, then I will do so. Because, yeah, some Muzzle Energy curves are better than others.

Jim Downey

Reprise: So, You Say You Want Some Self-Defense Ammo?

My friends over at the Liberal Gun Club asked if they could have my BBTI blog entries cross-posted on their site. This is the second in an occasional series of revisiting some of my old articles which had been published elsewhere over the years, perhaps lightly edited or updated with my current thoughts on the topic discussed. This is an article I wrote for Guns.com, and it originally ran 2/16/2011. Some additional observations at the end.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

You need to choose self-defense ammunition for your gun. Simple, right? Just get the biggest, the baddest, the most powerful ammunition in the correct caliber for your gun, and you’re set, right?

Wrong. Wrong, on so many levels. For a whole bunch of reasons. We’ll get to that.

Shooters have earned the reputation as an opinionated breed and arguments over ammunition are a staple of firearms discussions, and have been for at least the last couple of decades. Much of this stems from the fact that every week it seems, you’ll see “fresh” claims from manufacturers touting this new bullet design or that new improvement to the gunpowder purportedly to maximize power or minimize flash. And the truth is there have been a lot of improvements to ammunition in recent years, but, if you don’t cut through the hype you can easily find yourself over-emphasizing the importance of featured improvement in any given ammunition.

Perhaps it’s best to consider it by way of example. While the basic hollowpoint design has been around since the 19th century, I remember when simple wadcutters or ball ammunition was about all that was available for most handguns. Cagey folks would sometimes score the front of a wadcutter with a knife (sometimes in a precarious manner—please don’t do this Taxi Driver-style with live ammunition) to help it ‘open up’ on impact. Jacketed soft point ammunition was considered “high tech” and thus distrusted. And yet, these simple bullets stopped a lot of attacks, killed a lot of people and saved a lot of lives.

I’m not saying that you don’t want good, modern, self-defense ammunition. You probably do. I sure as hell do. I want a bullet designed to open up to maximum size and still penetrate properly at the velocity expected when using it. If you are ever in a situation where you need to use a firearm for self-defense, you want it to be as effective as possible in stopping a threat, as quickly as possible.

Modern firearms are not magic wands. They are not science-fiction zap guns. How they work is they cause a small piece of metal to impact a body with a variable amount of force. That small piece of metal can cause more or less damage, depending on what it hits and how hard, and how the bullet behaves. Here’s the key that a lot of people forget: as a general rule, location trumps power. All you have to do is meditate on the fact that a miss with a .44 magnum is nowhere near as effective as a hit with a .25 ACP. And when I say “a miss” I’m talking about any shot which does not hit the central nervous system, a major organ, or a main blood vessel (and even then it matters exactly which of these are hit, and how). Plenty of people have recovered from being shot multiple times with a .45. Plenty of people have been killed by a well-placed .22 round.

Hitting your target is what is most important and for most of us that is harder to do with over-powered ammunition we’re not used to shooting regularly. Chances are that under the stress of an actual encounter, your first shot may not be effective at stopping an attack. That means follow-up shots will be needed, and you’d better be able to do so accurately. If you can’t get back on target because of extreme recoil, then what’s the point of all that extra power? If you can’t get back on target because you’ve been blinded by the flash of extra powder burning after it leaves the muzzle, well hell, that’s not good either.

Nestled up alongside power is having an ammunition that will actually work well in your gun. Some guns are notoriously ammunition sensitive and you don’t want to just be finding out your gun doesn’t particularly care for an ammo when you really need it to go boom. Check with others (friends or online forums) who have your type of gun, and see what ammo works for them. Then test it yourself, in your actual gun. Some people won’t carry a particular ammunition until they have run a couple of hundred rounds of that ammunition through their gun. Personally, I’ll run a box or two through the gun and consider that sufficient; you’ll know after that if your gun generally handles that ammunition with any problems.

So, once you have an idea of what ammunition will work in your particular gun, how do you choose between brands? As I’ve previously discussed, you can’t necessarily trust manufacturer hype. So, how to judge?

Well, you can do some research online. The fellows at The Box of Truth have done a lot of informal testing of ammunition to see how different rounds penetrate and perform. The Brass Fetcher has done a lot of more formal testing using ballistic gelatin. Ballistics By The Inch (which is yours truly’s site) has a lot of data showing velocity for different ammunition. And most gun forums will have anecdotal testing done by members, which can provide a lot of insight.

But don’t over-think this. Handguns are handguns. Yeah, some are more powerful than others, but all are compromises – hitting your target is the single most important thing. And like I said, ammunition can help, but only to a certain extent. We’re talking marginal benefits, at best, whatever the manufacturers claim. So relax; all of the big name brands are probably adequate, and you’d be hard pressed to make a truly bad decision, so long as the ammunition will function reliably in your gun and you can hit your target with it.

Of course, as you do more research, and get more experience, you’ll probably find you like some ammunition more than others, for whatever reason. That’s fine. It just means that you’re ready to join in the (generally genial) arguments over such matters with other firearms owners. Welcome to the club.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Some additional thoughts, six years later …

Bullet design has continued to improve, with new and occasionally odd-looking designs and materials being introduced regularly. Some of these are *really* interesting, but I keep coming back to the basic truth that the most important factor is hitting the target. No super-corkscrew-unobtanium bullet designed to penetrate all known barriers but still stop inside a bad guy is worth a damn if you miss hitting your target.